All's going well, till someone tells you that you can't do any of these things unless the people in the photos give you permissions to sell pictures of them. This and other virtually identical scenarios illustrate a most common situation in which a photographer has to decide whether he needs such permission. Whether it's a school game, a music concert, an amusement park, or a professional-league game—the circumstances may vary—but it's all about the same thing: What are people's rights concerning their own likenesses, and what are your rights as a photographer to use those photos? What about the publisher? What about the people who buy photos from you? Because people have rights, there are conditions in which photos of people (and things) can't be used without their giving permission. So, the best way to get that permission is by their signing a simple agreement that says, essentially "it's ok." In the photography and publishing world, this agreement is called a model release. The term "model" relates to the fact that a photo of a person (or thing) is a "representation" of sorts. The term, "release", refers to the legal expression, release of liability. That is, one person has rights that they agree they will not exert under some conditions. They are "releasing you from liability." Once you have a signed agreement, the common vernacular is to say that your photo has been "released." The thing is, not all uses of photos require consent from the person. And if a photo does release consent, who is it that's actually liable? What are the penalties if any? Who doesn't bear any liability risk? There is a huge list of situations and conditions that can swing either way, and almost all of these conditions stand on their own—they're all intertwined with other conditions. If A, but not B.... Or, if A and C, etc... At this point, you're looking at the length of this chapter and thinking, "oh boy, I don't want to read all that." (Indeed—I didn't really look forward to writing it!) So, let me first point you to a short-cut. If you're not a professional photographer, then just skip right down to the bottom and read the summary. If you are a pro, you can also start at the summary because I know you're too darn curious to get to the bottom line. So, go ahead and read it. I'll wait here.

Ok, you're back? I assume you now have a good bird's eye view of what

we're dealing with here. And since you're back, I'm sure you're dying

to know the answers to your questions, because of course, your

particular circumstances are so unique and no one else has yet to

address them. Ok, fine. So now let me address the next question on your

mind:

Because you aren't necessarily going to get access to an FA lawyer, your next option is to speak to a general-practice lawyer, which is where things usually start going badly very quickly. FA layers often joke that 90% of their business comes from clients who got into trouble because they took the advice of non-FA lawyers in the first place. If you're one of the few that actually does speak to an FA lawyer, the next problem will come up:

Let's take a break for a sanity check. Do you follow all this so far?

If not, you should read Model Release Primer, which explains just

who is ultimately responsible for a photo of someone being published

without a release. Most lawyers don't know these critical factors of

publishing and the First Amendment. Therefore, they will cite risks—

even realistic ones—but you're not the one at risk. Someone else is.

That said, that someone could be your client—the one who licenses your

photo—in which case, they, too, know the risks, and may not license

the photo unless it has a release.

Technically, the release used at the top of this page is sufficient for any use you may ever need. However, the business caveats are simply that it is written very heavily weighted in favor of the photographer (and his licensees), and not really toward the person in the photo. In other words, it's very broadly worded, and is so permissive, you may not necessarily get anyone and everyone to sign it. This is particularly true of professional models who would prefer (if not demand) that more limitations be stipulated (such as a narrower scope of use, like a singular and particular ad or publisher). Such caveats aside, most common people that you might photograph candidly on the street or in public don't care that much and will probably sign it without giving much thought to it. If you ever get push-back on this sample release, you could always modify it by simply writing in extra provisions, even on the back, and even in crayon. It simply doesn't matter, so long as it's signed. For example, you may take a picture of a kid scoring a soccer goal, and ask the parents to sign the release so you can license the photo to the local sporting goods store. If the parents resist because the scope appears too broad, just write in "to be used only for ads for Joe's Sporting Good Store", or whatever the name happens to be, and you're done. There's no need to get really formal about this stuff. One more thing: There is no government mandate about when a release is required. That is, the government does not track down violators. It is strictly a matter of civil law that must be enforced by individuals themselves. People have rights to privacy and publicity, but the First Amendment of the US Constitution also grants freedom of expression. It is this mixture of rights that often run counter to one another, so what a model release does is remove that conflict. As its name implies, it "releases" one party from liability for having violated the other party's rights.

And here's where things get sticky. What are those conditions? When do they apply? The very short and simple answer is easy, an example of which can be found in California Code 3344. It has multiple sections, but section (a) says: "... Any person who knowingly uses another's name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness, in any manner, on or in products, merchandise, or goods, or for purposes of advertising or selling, or soliciting purchases of, products, merchandise, goods or services, without such person's prior consent, shall be liable for damages." Looks simple, right? Well, it is and it isn't. The simple part is the notion of "promotion"—the fact that people have the right to control if and how others use their likeness to promote an idea, product or service. Where it gets complex is what actually constitutes a product or a promotion. Remember, the First Amendment allows for freedom of expression, which includes art forms, opinions, newsworthy information and other forms of information. Because of these complexities, people simply disagree: you may think the photo of you on a website is a form of promotion, whereas the person that owns the site simply regards it as a demonstration of his artwork. Which is correct? Whose rights outweighs the other's? Well, that's what courts are for. But until it gets there, people turn to... well, each other. And most people are just not well informed on the subject. It is probably the most misunderstood topic in the world of photography, which makes it ripe for misinformation running rampant. Whether it's verbal hearsay, or rumors that spread in internet chat rooms, the mistake people make is trying to simplify into a few words a topic that cannot be simplified. And then people cite anecdotal experiences. For instance, if you were to hear about a case in which someone was sued for taking a picture at a soccer game, don't simply assume that one cannot take pictures at soccer games, or any other kind of sporting event. This is how rumors spread. The basic facts of that one case are usually misinterpreted from the outset, and those who spread rumors usually fail to follow these cases, which are often dismissed as "frivolous" anyway. The reality is that almost every case is different, because the conditions that trigger the need—or lack thereof—for a model release are tightly intertwined and interdependent on multiple factors. It is more the exception than the rule to establish conclusively the necessity of a release for any given image.

Another critical point: many people make their assumptions about when

releases are necessary because they were told by a photo buyer, be

they publishers or stock photo agencies. It may be that they want you

to have releases for photos they use, but this does not mean that

the use actually requires a release. The two are distinctly different.

Publishers are fearful of being sued, and having a release alleviates that

risk. Of course, this is a perfectly good reason for them to be cautious,

which also underscores the main point that publishers are the ones who

are sued, not photographers. Accordingly, the more images you have that

are released, the wider your potential audience of buyers are. But, do not

confuse the desire for a release with a legal need for a release.

These are very different things, especially when you have business

considerations at stake. Simple example: just because you have a great

photo of someone that didn't sign a release does not mean that you

shouldn't try to sell it—if it's a great shot, you may make some pretty

good money with it. Money that you wouldn't have gotten if you wrongly

assumed that you couldn't sell it because you didn't have a release.

You may have heard the term, "commercial use," and that model releases are necessary for all commercial uses. It is true that commercial uses of a photo are those where the picture of the subject (person or thing) implies an advocacy, like those you see in advertisements. But, you need to think beyond just that kind of advocacy. If the use of the photo implies that the person agrees with the underlying message or the person or company that paid for the use of the photo (like that of an advocate for a non-profit company), then a release is still required. For example, a publisher can't just place a photo of a person on a poster that says, "support your local hospital," just because this is not a "commercial use." The photo would imply an association between the subject of the photo and the user of it, and that's what triggers the need for a release. Similarly, if the use of the photo implies that the publisher of the photo is speaking for the person in the photo, again, this requires a release. For example, a photo of a musician that says, "I never go on stage without my guitar," even though the use of the photo never advocates a specific guitar company or other product. The fact that the user of the photo would appear to be speaking on behalf of the person in it, a release would be necessary. Well, a release would be necessary unless it were a direct quote from that person, and the use of the photo is merely repeating something he's said in public, or to a reporter, for example. When this is the case, we enter into the realm of "editorial use," where a release is not necessary. Magazine and newspaper stories about people (famous or not) do not require releases for the photos because the article is merely an expression of free speech, and no one is assuming that the person the article is about necessarily advocates what's being said. Indeed, many magazine articles say things that the subjects would prefer not be said, but a release is still not necessary because that's the whole point of freedom of speech: to report news and information. You would only get into trouble if you lied about them in a way that harmed their personal or professional life. That would be a case of libel, and is beyond the scope of this topic. So, the general rule to think of is whether the use of a photo would imply that the subject "agrees with" or is a "sponsor of" the user of the photo, versus whether the use of the photo is more about the subject that the average viewer would not assume the subject would necessarily agree with, or disagree with. There are so many examples of each of these kinds of "commercial" or "editorial" uses that it would be impossible to list them all here, or anywhere. So, don't expect to learn specific examples like "advertisements" and "magazines stories." Yes, these are obvious, but learning involves understanding why those are as they are. Instead, you need to think about the basic concepts, just as I described them above. Granted, this is vague, but it's something you eventually pick up on quickly as more examples are provided. (Or, as you merely witness real-life things you see everyday.) Similarly to advocacy, there's the question of whether you may be using "features" of a person or thing—such as whether they are well-known celebrities or iconic logos—which may also trigger the need for a release. This is similar to the "association" concept, but rather than suggesting that they are "advocates or supporters" of an idea, the use of the image could be exploiting their inherent recognizability and "goodwill" to enhance the perceived value of a product or idea. (Also see Photographers' issues concerning trademarks and photography.)

For example, a well-known school textbook company using an unreleased image in an educational context does not require a release. However, if a religious organization wanted to use an image, they're almost assuredly going to need a release, because people have a right to be associated (or not) with religious points of view. So, if there is any hint of religious dogma, bias, or promotion, privacy law doesn't recognize the use of the image as "editorial." The easy test is to look at who the publisher is. If it's a religious institution, or if there any any affiliation with a religious person or organization, chances are really high it would be regarded as a use that would require a release from the subject of the photo. Quick quiz: if you were to sell them such a photo, do you need a release? You should know by now that you don't—they do. But because they do, they would be unlikely to buy it from you unless you had it. All this is making sense, right?

Good, because there are multitudes of exceptions that will surely throw

you off. A careful understanding of those caveats is important, as will

be discussed next.

The following checklist of four items is a handy tool you can use to determine whether a model release may be necessary. As you read these, you can get a sense for what publishers need to consider when licensing a photo from you. Though you, the photographer are not liable for whether the photo has a release (you can always sell an unreleased photo), you make more money when you have releases that permit buyers to use your photos. Knowing when releases are necessary and when they are not helps you match up (and market to) those buyers that may need either kind of photo. That is, for your photos that do not have releases, you can market them more profitably to editorial buyers, whereas those photos that do have releases can be more successfully marketed to commercial users as well.

If you can't, the buyer doesn't need a release. Though there could be some rare exceptions with matters of privacy that most everyday people don't run into, you can rest assured that unless people are clearly and unambiguously identifiable in a way that a judge would be able to say, "yes that's him," you don't need a release. (For a discussion of those exceptions of those rare exception of privacy, see this page.) So, if you can identify the person, does that automatically mean you need a release? Not yet. You have to go to the next item.

Commit this statement to memory: Unless and until you have a specific use for an image, it doesn't make sense to ask whether a model release is necessary. Why? Because of "association." The photo itself does not draw an association between the person in the photo and someone or something else unless a use for the photo exists. Otherwise, there is no "something else" to associate with. Once a use for the photo is determined (because someone wants to license it from you), then you can now consider whether that use would imply an association—or rather, whether the person in the photo would be assumed to be an advocate or sponsor for the product or idea that the user of the image is doing with it. Some uses require a release. Some do not. Some are vague. Since drawing an association is not always obvious (and is easily disputed), you have to look at other things to strengthen the argument on whether a release may or may not be required.

No photo can be used at all if any laws were broken, such as "breaking and entering" into someone's home, invasion of privacy, or placing a hidden camera in a workplace. Because these acts violate existing laws, the legality of the photos are moot. Assuming no laws are broken, shooting in public places provides the most latitude for licensing unreleased pictures of people, even if they are identifiable. "Latitude" does not mean "permitted"—it means that the bar to clear is higher than if the photo was shot in a private setting. For example, a photo of a large crowd of people to be used on a billboard ad for a cellular company my have some recognizable faces, but unless it appears that such people were "advocates or sponsors" for the company, a release from them wouldn't be necessary. Judges (and most objective people) can tell whether a photo trips such advocacy wires, so don't talk yourself into thinking there is ambiguity in a photo because of the person's expression on their face or because you don't think there is a notion of advocacy. You really have to learn to think objectively about this. Of course, what I mentioned above is a "commercial" use of an image: a billboard ad for a cellphone company. As you no doubt know, a release would not be necessary at all if the use is for editorial purposes, such as a newspaper story or magazine article about a subject. Here, photos of recognizable people and things (copyrighted and trademarked items) taken in public for editorial publication is called "fair use." We'll touch upon all this again—after all, this is just the checklist to review—so don't worry if you're not getting it all immediately. On that note, there's one more checklist item that needs to be noted:

Please refer to

this section

for a thorough discussion.

Let's go through each of the items on the checklist and examine more

closely what its implications are. Remember, it's rare that one and only

one checklist item triggers the requirement for a release, or that it

permits the use without a release. Many factors have to be weighed together.

Ok, so now let's assume you have a clearly identifiable subject. If you were establish (using later checklist items) that you do need a release and you don't have one, a publisher can still use the image provided that he removes identifying features. One way is to digitally alter the image to make the person unrecognizable. "Rubbing out" an otherwise identifiable face is perfectly legal. In fact, you see this all the time in video broadcasts, such as those commercials that advertise weight-loss programs, where a face is usually "pixilated" or "smudged," leaving the rest of the person clear and visible. Because the publisher can rub out a face, he can reduce his liability accordingly. You don't need to do this, nor should you—you're not the one who has to, or that can get in trouble if the publisher doesn't do it. You're just providing the content, so as the photographer, you can sell the image to the client, even if you don't have a release and the use of the image would require one. Now, let's go back to that issue of the "crowd" shot again: what if your picture was of the entire field of kids playing soccer. Although you can still identify some people individually, it's been successfully argued that if the point of the photo is not a specific person, but a broader scene, then a release is not necessary. Tying a single person from that crowd to a promotion of an idea has not been ruled as a legal liability. A crowd dilutes the perception that a particular person is tied closely to an idea or promotion. If the crowd were a cohesive group—like a particular religious congregation—then there may be case for their making a claim as a group (or their organization can on their behalf).

On the other hand, a religious use of an image of a person can be

problem. For example, even though posters and postcards usually do not

constitute a commercial use, a litigant once sued a postcard company

for the use of a photo of him, not because of anything to do with the

photo, but because the company used the proceeds to support the Mormon

Church, thereby implying that the person was an advocate of the Church.

The point is, once again, that use has a great influence on whether

a release is needed, bringing us to the next item on the list.

Also, money has no bearing on this from a legal point of view. That

is, whether you sell an image for thousands of dollars, or give it

away for free, the transaction itself is irrelevant. It is only how

the image is ultimately used does it potentially infringe on the rights

of others.

The legal test is a simple question: is there a reasonable chance that you are in a situation where someone could photograph you? If people are standing around with cameras, then the answer is yes. It doesn't matter whether people are "allowed" to take pictures, what matters is whether there's an apparent opportunity where you have a reasonable expectation that you could be photographed. If you don't want your photo taken, and you have a chance to leave, then do so. But some situations aren't like that—your own home, for example. Or some public settings like locker rooms, dressing rooms, bathrooms. These are examples where you have a reasonable expectation that you will not be photographed. Where this gets more interesting in when you "invite" people to be photographed—or, even when whether they invite you to photograph them. Photo studios are the most common example. Once there's a "orchestration" event, where there's a premeditated plan to photograph or be photographed, then the consent is granted for the "act" of being photographed, but the subject has not yielded any rights for how the photo is used beyond that. This is strictly a private matter, so far.

Because this has to do with privacy laws and rights, not publicity laws,

you are encouraged to read more about the topic in the article,

Personal Privacy and Model Releases (Saturday, April 12, 2008).

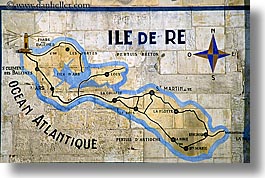

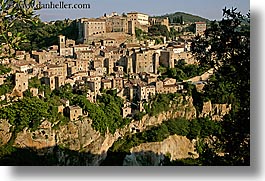

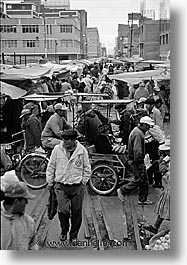

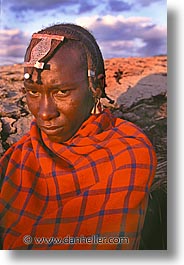

What's your analysis? Can you argue both for and against the need for a model release here? Let's start the discussion by looking at the first two questions: are the people identifiable? And, what is the use? If the people weren't identifiable, we could rule out the need for a release. But, since they are, it depends on other factors. So, let's look at those. We know the "use" because you're reading this text: it's editorial. That is, I'm teaching a subject. Note that not all "teaching" is necessarily considered editorial. Product manuals that explain how to use a device (such as a camera) is teaching, but it's coupled with the product itself, making it part of a more commercial endeavor than the sole purpose of education. If the manual were sold separately, then it distances itself significantly from the product. And if it was published by a completely different company (or self-published by the author), then this distances the book even further. If all this material were in a book that is sold for money, is it suddenly a "commercial product?" No—not any more so than how a newspaper is sold for money, and its content is purely editorial. How about the fact that ads are placed on the same page as this article? Again, no, just as ads are used in newspapers and that doesn't suddenly trigger the news articles as being commercial. Why? Remember the "concept" I told you: association. Just because there's an ad on the page—whether here, or in a newspaper, or on a blog—doesn't mean there's an association between the person in the photo as part of the article and the ad itself. And finally, could the person in the photo be considered an "advocate or sponsor" for the content discussed here? Clearly not, as is already self-evident. If I were promoting an idea or product, that would be different, and that gets into the beginning of the gray, ambiguous cases. At the forefront of these are religious and political "teachings." In these highly emotional subjects, true believers often feel they are simply teaching facts, but the courts still consider them "opinions"—well, for the time-being they do. In any event, such text is not considered editorial, so if photos are used, releases are almost certainly required. Yet, there are many things that can be considered opinions, or possibly products or services, and it's not always easy to know whether the photo subjects could be considered "advocates or sponsors." All the more reason why it's the publisher that ultimately carries the burden of responsibility for whether to use a photo without a release. If the subject were to object, the publisher has to defend its rationale for why a release wasn't necessary. Consider a picture of the head of the Supreme Court of the United States, looking directly into the camera, and a caption underneath saying, "I agree with this text." Clearly, this might be a problem because I would be suggesting that the head of the Supreme Court has reviewed this material, which he hasn't. It's not the photo that's the problem, it's the text associated with it. A publisher needs to be careful how he represents people, regardless of whether images are used. Alluding to the religious or political uses described earlier, there is an issue of misrepresentation to consider, but again, it doesn't apply here, as I am making no such statements at all.

The next question is whether the picture was taken in a private setting. For example, a photo studio in the shopping mall that takes people's portraits for a fee is a "private setting" because people aren't in an open space where they could be photographed by anyone at any time. They are now in a controlled setting and are there specifically for their picture to be taken, and for their own personal use. They aren't consenting to someone else using their photo. Otherwise, they wouldn't choose to sit for the photo. Obviously, a release isn't necessary for someone to get a photo of himself, and the photographer or the studio is not "using" the pictures. However, if the studio wanted to hang one in the studio itself or in the display window to illustrate the kind of work it does, a release would be required from the subject of that photo because the use is "commercial." More precisely, the studio is a specific place of business, and the display of a photo of someone would imply by itself that the person is an advocate or supporter of this business. This will come up again later when contrasting it to a web site, where this distinction isn't so clear. That is, "illustrating" the kind of work a photographer (or studio) does is separate from "promotion." In the example of the photo studio, is the fact that it's a "private setting" a trigger for the need for a release (for someone else to use/publish the image)? Not by itself it isn't. The "privacy" aspect only means that you're taking photos of someone that has not given up privacy rights—if they want you to take pictures of them in funny clothes, or doing what would otherwise be embarrassing in public, that's their right. And their act of letting you take their picture isn't under the same conditions as if they were out in public doing the same thing. The same is true of whether you ask someone to model for you, whether you pay them or not: if you're asking them to pose in particular ways, or to wear clothes, or anything at all, this is not a "candid" photo that can be treated the same way as those taken in the public. For a detailed discussion on shooting professional models (or anyone in controlled settings), see, Pro Models and Their Agencies (Wednesday, April 21, 2010). Another misunderstanding people have is the difference between "privacy" and "private property." In fact, the whole issue of "property" has been misconstrued by photographers over the tears to the delight of property owners. Property itself has no implicit rights the way people do. Photos of property has to be "protected" either by trademark law, or in some cases, copyright law.

In brief, it says that a contract can only be enforceable (and defensible) if there is "consideration" (compensation). If there is no consideration, the law calls it, a gratuitous promise, where one party agrees to do something in for or without reward. Courts will uphold this promise for situations such as pledging a donation of money to a charity, but not if the party has relinquished a right, which is precisely what a model release is doing. Hence, it's a contract, not a promise, and therefore consideration must be given (and the contract should say so to avoid disputes later). Consideration doesn't have to be money; it can be anything. Even barter. It just has to be something of "value," or as is used in legalese, "for valuable consideration." Because this is vague, most courts interpret this as being whether the contract entered into between the parties were done in full awareness of what they were getting into. So, if you write into the model release that you will give the subject a fake Rolex watch, and the person agrees, a judge would probably say that's ok. But, if it says you'll give them a verbal compliment, a judge might have a problem with that. Obviously, the item of value must be a "legal" item—recreational drugs are not going to look good in a judge's opinion, regardless of how much "value" they may have. A more typical example is where one goes on tour with an adventure travel company. The clients sign a liability waiver that includes "model release" language as well, and the consideration in this contract is the simple fact that they are going on the trip. The same kind of thing can be found on admission tickets for certain performances (where they may have a photographer take pictures of the audience), amusement parks, and other private events where the public pays to enter. In some of these cases, people agree to have their likeness used (if their photo is taken), whether they are aware of it or not. Now, strictly speaking, it's unlikely any of these companies will use such photos without asking people directly anyway, simply because of the bad press they'd get if someone were to complain. But the point of this section is merely to point out that the "valuable consideration" portion of the contract can be satisfied by many things.

Some photographers like to offer someone $1 to sign a release. This is fine, but if you plan on shooting a lot of people and getting a lot of releases, you're going to lose a heck of a lot of dollars, all for photos that are highly unlikely to ever be used or licensed by anyone else (and even then, they aren't necessarily likely to need a release). It may be easier to just offer to email them a copy of the photo(s) you take. Here, you can get contact information (which you need anyway), and you're done. Professional photo shoots usually involve a modeling agency, which will produce a release for you to sign, binding you to limitations for what you can do with the photos. Usually, the client and use are known ahead of time, which is written into the contract.

Note that not all states require consideration. New York doesn't. You can

have someone sign a model release and give them nothing. In fact, you can

even insult them. (Some New Yorkers actually do this as a matter of

professional courtesy.) Either way, the model release "contract" is still

valid. Every state is different, so if this matters to you, check with

your state's website.

Relax, and commit this to memory: people sue either because there's a perception of easy money (usually, a false one), or because they're just upset about how an image was (or will be) used. If they are upset, they may threaten you till they are blue in the face, claiming to get a lawyer and sue you. They may even get a lawyer. But once they do that, the lawyer will quickly inform them that, unless something is done with the photo, nothing can be done. In this case, the lawyer may grandstand saying that you're in trouble, but this is just a performance. They can't do anything to you because you haven't done anything with the photos. And if you did happen to license it to someone who published it, then they go after the publisher, not you. About lawsuits: it's expensive to sue someone. Incredibly expensive. The cost of hiring a lawyer to sue you is so exorbitant, that unless you are both egregiously guilty and stinking rich, you're worrying over nothing. Of course, this is not a green light to publish nude photos of your ex-girlfriend because you happen to be homeless and living under a bridge. You also don't want to be burdened by the "hassle factor" of getting badgered by annoying letters from angry people who "threaten" suits, even though they will eventually learn they can't afford to sue you. Millions of photos a year are published without a model release in ways that, if accompanied by a litigious lawyer, would end up in at least a healthy settlement. There are fewer suits on wrongful publication of images than there are tax audits, lottery winners, or elephants that stand on one leg at the circus. It's just a very rare event, and usually limited to high-profile celebrities where their images have financial value. Lastly, remember that you're in business to make money, and business is about relationships. Regardless of the law, you want people to be happy, especially with you. No matter what your circumstances are, the best way to handle any kind of dispute is not by trying to explain the law to someone. That never works. Instead, allay their fears about how their images may be used. If they're really irate, just say you'll never ever use them. (At such a point, the goal is nothing more than to end the argument.)

The risk of legal entanglement is not something that should scare you out

of the photo business, or even cause you to limit your subjects to birds,

bees, snow and trees. Yet, I don't want to put you too much at ease: these

are important issues, and guidelines should be followed to the best of

your abilities. Just don't worry.

There are upsides and downsides to the prospect of getting a subject to sign a model release. Because people don't always take well to being asked to sign a release (timing is important!), you can actually cause yourself more headache by trying to get a release than if you just took the picture and dealt with it later (or not at all). By having a better understanding of certain realities, you can find the best balance between the upsides and downsides of doing business. To understand the framework for this line of discussion, let's make it easy by defining two easy and obvious ends of a spectrum. On one end, if you're not in the business of photography, and you're just an everyday person that took a snapshot of something—anything, like a rock star at a concert, a woman cooking, or a professional baseball game—and someone says to you, "Hey! Can I buy a print of that?" You can. Why? Because making a print and selling it is not implying that the person in the photo supports or advocates an idea, product or service. Some often point to the photo itself as the product, but this is where "art" comes into the picture, which is another subject discussed below in this section.

Big companies always have to be careful about what they do when it comes to the public because of susceptibility to lawsuits. Even baseless claims are costly to defend, and unscrupulous people are known to go after large media companies for photo usages, even though 99% of these claims are without merit. Their best defense against this is to only use released images, even if a given use doesn't require one. Yes, this very practice is what causes most people to completely misunderstand when and why model releases are necessary. Just because a media company gets a release from someone for a particular use does not mean that a release was necessary. It means they are reducing the chance of a frivolous lawsuit. They need to do this because they are high-profile and have tons of money. Do you need to protect yourself from a frivolous lawsuit? That's up to you to decide, and that's part of the risk/reward analysis.

One of the biggest mistake photographers make is assuming that they

have to follow the same "behaviors" as big companies do because, well,

they must know something the little guys don't. This is a fallacy. Big

companies do things because their risk assessment require them to be

that way. This does not necessarily translate to your business (if you

are in business), or your risk level.

At this point, let's review some common issues that people face every

day on the question of whether (or how) a release may or may not be

required. As you read through them, you may gain a better appreciation

for just how complex circumstances may become.

Many who know a little about fair use usually only know a subset of the many definitions it can entail, and if they aren't familiar with how it pertains to photography, this section can be confusing, or worse, appear misleading or unrelated. But they are related, so let's back up and look at it from a conceptual viewpoint. The presumption of fair use is that when "things" (people or objects) are in public view, they can be used in any manner that is protected by The First Amendment. Many kinds of speech and expressions are protected, but then, many aren't. You can state your opinion freely, but you can't damage or cause harm to someone's reputation through misinformation (e.g., lying). Obviously, this is really tricky stuff, and we don't want to get buried in this banter again, so let's just step back and look at photography. The spirit of "fair use" means anyone should be aware that he could be photographed at any time by anyone. One cannot stop the photography process from taking place, even though a subject still has some rights for how those photos may be used. This is in contrast to private settings, such as going into someone's home, or in a bar or at a concert. Under those conditions, someone actually has the right to stop you from taking pictures. This is usually stated on an admission ticket that has fine print that says, "no cameras." Obviously, you see people there shooting anyway, which may cause you to think, "are they breaking the law?" No. It just means that the property has a right to stop you from doing so if they so desire. It's up to them to enforce their rights or not. Turns out, most places don't mind that pictures are taken either. So why have the restriction? There could be a variety of reasons, such as how some photographers can be disruptive, or the property may have certain items they don't want photographed, or there may be trademark concerns. For further discussion on that, see Photographers' issues concerning trademarks and photography. Interestingly, despite the fact that you may have taken photos against the policy stated by the admission ticket, this has no bearing on the limitations of your right to license those images. This is because properties (and animals) do not enjoy the same privacy or other protections by law that people do. I'll touch upon this in the next section on Property Releases.

Now, in practical reality, the only people who really care about this

are high-profile, famous, or rich celebrities who derive some of their

gazillions of dollars of income from the sales of their own photos, shot

by their own (work-for-hire) photographers. They also don't want to see

"bad" pictures of them bubbling up all over the place, so they restrict

photography to control their appearance. If you're just at the local

bar and are watching a band, you should certainly feel free to take

pictures. Who knows—you could get a new client.

So, why do most photographers think they need releases of buildings? The short answer is: history. Because image buyers don't want to be sued by anyone for any reason (remember, people sue if there's a perception of easy money), such buyers only license images from photographers that have releases. Doesn't matter what the photo is of—people, places, or things—if there's something in there that could cause a litigious lawyer to go after the publisher, the publisher doesn't want to be exposed. So, many will only buy (and use) released photos, even though they know perfectly well that releases may not necessarily be required for any given use. Most publications use thousands of images for each published periodical (book, magazine, newspaper, advertisement), and they do thousands of these per month. They simply don't want to have to think about whether each and every photo needs a release. It's already a complicated subject, so when you're dealing with thousands of photos on a regular basis, you just want to play it safe by only buying released images, and making that the standard operating procedure. So, for years, photographers heard from their buyers, "Only give us released photos." The photographers then got into the habit of only sending them released images. But what got lost in the message is the reason; they mistakenly believed it was because releases were required, and they also mistakenly believed they were at risk, not the publisher.

So, are you similarly exposed if you try to sell unreleased photos? No. Remember from Model Release Primer that it's only the publication of photos that requires a release. The sale of photos does not require a release. Therefore, you do not need to obtain a release from the owner of the building or any other kind of property just to sell or license the photo to someone else. It is entirely the buyer's responsibility to (1) know whether their use would potentially violate the trademark, and (2) if so, to obtain permission to use the mark. If this is the case, why do some stock agencies require releases for photos of buildings and/or people? The "gentle" answer is that the agencies just want their buyers to be assured that the images they use are safe—that they won't be sued. The agency wants to have a good reputation for having publishable content. The less gentle answer is that most agencies have no idea what the law really requires, and are simply misinformed that they think they need releases to sell the photos in the first place. In actuality, the mere publishing of photos of buildings (or other trademarks) would rarely, if ever, constitute a trademark violation, and most publishers are less skittish about this as they used to be. What's more, the internet has grown to such a degree that most publishers are small companies or individuals; they either are unaware, or they just don't care. This is an odd circumstance where ignorance yields a more intelligent policy. What's more, trademark violation cannot be done merely by publishing a photo, like it can be done for pictures of people. The photo itself is not a violation of the trademark, but the text associated with the photo that would cause it to become so. This is why it is impractical (if not impossible) to know whether any given photo of a building (or any trademarked item) would require a release unless and until there was an actual, known design for how the image would be presented in publication. For it is then and only then could one look at it and say, "yeah, that would require a release."

The net rule of thumb is, the more easily you can get a release for a photo of a trademarked item, the less you actually need it. If it starts getting expensive—an expense you shouldn't pay for—then the more likely it is that a release would be required.

This entire subject is far more complicated once you get into

details of atypical uses and subjects. So, you should read

Photographers' issues concerning trademarks and photography, and get informed. In any event, taking

photographs of (or on) buildings or personal property is always legal,

as is selling such photos to others. While the actual publication of

such photos may require consent, be sure not to confuse the two: selling

isn't the same as publishing insofar as consent is required.

If you're looking to make a calendar of cute animals, and you're using candid photos you took in public, you are free to do so without releases from the animals' owners. On the other hand, if you photographed the animals in a private settings, not in public view, such as a photo studio, you need to get a release because it's a private business transaction, where the person who paid for the session did not give up his right to privacy—and that right includes his presumption his actions (of being photographed with or without props) is not to be made generally available.

This provision of privacy applies to people, too. When you're engaged

in an arranged photo shoot at the request of either the subject or

the photographer, the person has not waived his inherent right of

privacy, so the photos taken during that session are privacy unless

the person waives that right. In such cases, a release would be

required if someone wanted to publish the image for any

kind of publication, editorial or commercial. (Please see

Personal Privacy and Model Releases (Saturday, April 12, 2008)

for more information.)

And by the way, to get a sense of how all of this can easily be argued

in the other direction (despite what courts say), see

this article. I don't have an opinion one way or another—just presenting the various

points of view.

You can also sell these pieces because, as you may recall from Model Release Primer, profit has nothing to do with whether a release is required. ("Profit" can certainly affect the amount of damages can be recovered later, but only after a determination that a release was needed in the first place.) This is another one of those mass-disinformation internet rumors, that "art" suddenly becomes "commercial" because it may be sold for money. Granted, it's not always clear when art is considered as such for any given work; indeed, many commercial efforts have tried to masquerade themselves as artwork. but an educated eye can tell the difference—as you may recall, the ultimate test is whether the average person would assume an implied support or advocate association between the artwork and the person or thing depicted. For example, in the case of Nussenzweig v. diCorcia, Defendant Philip-Lorca diCorcia's show "HEADS" appeared at the Pace Gallery in Chelsea (Manhattan) in September and October 2001. The exhibition featured photographs of 17 people taken without their knowledge in New York, Tokyo, Calcutta and Mexico City. The photographs, tightly focused on their individual subjects and printed at four-feet-by-five-feet, created uncommonly intimate likenesses. In addition to the Pace exhibition, the photos appeared in a catalog and numerous advertisements and reviews. This court case was also the basis for a decision for a dispute between a top photographer and the Orthodox Jew whose picture he surreptitiously took at Times Square, then sold 10 prints of at $20,000 to $30,000 each. As commerce, the picture would be subject to a model release; as art, it would not. Supreme Court Justice Judith J. Gische has ruled it is art. In another court case, Mattel, Inc. et al. v. Walking Mt. Productions, which you can read about here, Mattel sued an artist and his company for copyright and trademark infringement based on the artist's use of BARBIE dolls in a series of photographs depicting them in various unflattering poses, and use of the BARBIE mark in connection with the photo series. The court found that the photos are permitted under "fair use" professions, which precludes Plaintiff's trade claims. Furthermore, the artist may sell postcards featuring the same photos displayed in the exhibit, since an artist is permitted to sell his own artwork in other formats. In the court's opinion, the average person would not necessarily assume that the Mattel company was an advocate or sponsor for the photos depicted.

Publishing photos of recognizable people in editorial books (which includes almost all books) never requires releases (though publishers often ask for them anyway, as discussed earlier, and in Model Release Primer.) Many photographer forums say that book covers are exceptions (the thinking being that the cover "sells the book"), but this is untrue. The 11th Circuit court ruled on July 18, 2006, "amazon.com did not violate a person's right to privacy or commerce simply because the photo was used as the cover of the book." (The court case and the circuit's opinion is written here.) The exception to when "art" isn't really art, brings us back to the example where you have a portrait studio in a shopping mall. Remember my point about posting a photo of someone in the store to demonstrate your work? That's a commercial use because you are promoting your business. Here, the photo—or "art" in one of its forms—is being used in a commercial context because it is very specific to the nature of the business. This is quite different than a restaurant, where artwork is not so clearly a part of the establishment's "business model." Here, it's more widely accepted as being part of the decor. (One can argue that decisions to eat at a place aren't based on its artwork.) What's more, it is generally accepted that eating establishments have always been venues for art. This de facto standard has been established long ago, and courts usually uphold such traditions.

However, an exception may apply if the exhibit were displayed in a way that would make the exhibit appear to be more of an advertisement. For example, American Express, the credit card company, once sponsored an exhibit of photographs from Annie Liebovitz, where her portraits of famous people were portrayed. While the US Constitution provides a person the right to control how their likeness is used for advertising and promotion, the legal statutes indicate that there must be a direct connection between the person portrayed and the product or service being advertised. In fact, California's Civil Code 3344(3) specifically says The use of a name, voice, signature, photograph, or likeness in a commercial medium shall not constitute a use for which consent is required under subdivision (a) solely because the material containing such use is commercially sponsored or contains paid advertising.If Annie Liebovitz's exhibition were only underwritten by American Express, consent from the people in her photographs would not be required, even if the entire exhibit was overrun with ads and promotions. But in this case, under each large portrait was a copy of an expired American Express card that was once held by that particular celebrity. This establishes the direct connection between the person and the company, so their consent would be required from each such case.

A less clear case would be if there were an art exhibit sponsored

with an effort to raise money for AIDS research. Here, the legality

isn't so much in question insofar as publicity goes; the real liability

here is that of privacy. The law provides protections for people's

reputation and livelihoods as well, and someone could make the case

that they have been harmed by the implication of being affiliated with

the cause or the disease. This would be a difficult and ugly public

dispute, of course, but the point here is to recognize the difference

between being associated with a commercial expression, where someone else

benefits from someone's photograph, versus a personal expression, where

the photo subject himself might be harmed. Discerning between the two

is not easy.

You can even sell them. Whom you sell them to, and what they choose

to do with your photos is another thing entirely. So, even if you're

unsure about how you can use an image, keep this in mind: if you

don't shoot the picture, you've lost a potentially great image and

a potential sale. If nothing else, you could have put in your

scrapbook. If you can somehow manage to get a release later, or if

you want to use the image in an editorial context, you always have

that option. The rule of thumb is, shoot first, and ask questions later.

As you know from reading this chapter so far, if you're the photographer, you own the physical media to pictures you shoot, but it doesn't mean others have the right to use those pictures commercially. (That's why you want to get a release.) Conversely, however, if you're not the photographer, it doesn't necessarily mean you can use pictures of yourself either. Why? Because you don't own the copyright to the images. Yes, the photographer owns the copyright to the "work," even though the subject owns the right to his own likeness. Normally, you get around this by purchasing (or coming to some other agreement to acquire) the image(s). This "license agreement" is the method by which one obtains those rights. The terms of that agreement is what sets limitations on either or both parties. So, the lesson: "usage" and "ownership" are two very different matters. You can own images, but not have the right to use them. You own the rights to yourself, but unless you have a legal access to the copyrighted work, you can't use them either. To clarify a common misconception about the relationship between ownership and rights: regardless of whether the subject grants rights to a photographer, it does not mean the subject can demand the physical media from the photographer. The media always remains the property of the photographer, regardless of whatever rights he may or may not have to use it. If the buyer is the subject of the photo, then he can obviously do whatever he wants—he owns both the media and the rights to it. But if the buyer is not the subject, the sale of the physical media does not transfer the rights to use it. There are broad implications of this: if someone takes a picture of you, even if it's against your wishes, you do not have a right to confiscate the media. Similarly, if you take a picture of someone else, you are not required to forfeit your media just because they demand it. (Note, the only time someone can prohibit your taking a photo is on a private property as discussed earlier.) The point to all this is that the use of an image in a commercial context (only those where a model release would be required) requires cooperation from both the photographer and the subject. Neither can use the image without the consent of the other.

The legal case that most legal analysts point to is Corbis vs. James Brown. While this case was never adjudicated because the parties ultimately settled out of court (after appeals that didn't appear to favor either side), my interviews with legal scholars, reporters and judges who were familiar with this case felt that the case would not have changed the current law—that sellers have any liability for how publishers use (or misuse) images of others. The primary issue they cite is the countrary argument: if sellers were in the position of being held accountable for how a buyer published an image, publisher's would no longer bear such responsibility, and the rate of violations would skyrocket. If someone tried to bring a claim against the publisher, they would point to the Corbis case as precedent. That is, if someone sold them the image to publish, it must have been ok to publish. If it wasn't ok, then it's the seller's fault. Not only do courts not want such a scenario to take place, but courts also recognize they don't want non-liable parties in a position of making complex legal decisions on behalf of people they don't represent. Therefore, all legal analysts I've ever interviewed on this subject feel confident that the Corbis case would not have gone against them. That there is no other case where a seller was held liable for how a publisher used an image, it's reasonably assured that making an image available for sale does not require a model release. This includes any and all forms of publication and media, whether it's traditional print or online formats, including personal web pages, photo-sharing sites, social media sites, stock photo sites, or anywhere. The easy way to think about this is the simple case of a photo of a high school football player scoring a touchdown. You can put it up on your website and license it to a newspaper as part of its story on the game. The fact that its editorial means that a release isn't necessary. That you can sell it for such a purpose underscores the reason why you can place it for sale without a release. Just because someone else might want to license the photo in a way that would require a release doesn't suddenly mean you can't place it on your site for sale. Selling doesn't require a release, and you aren't required to know whether a given buyer would require a release for their particular use. It's out of your hands. Again, see Model Release Primer. However, you still need to consider the "affiliation" implication, and this is more of a design consideration of your website. That is, you can display images for sale, but if your use of an image would somehow suggest that a given person is affiliated with you, or advocates your (or anyone else's) business—rather than just your selling the photo—that could require their consent. Obviously, this is highly subjective, and accordingly, people tend to swing in extremes on this. You can either use an image for which you already have a release, or just choose a different design for your page.

Using common sense to see whether an objective observer would consider a

given photo as a promotion of an idea, product or service is your best

guide. The fact that you're selling those photos is not the same as

the promotion of them. A web page that sells photos of people is not

the same as a catalog that sells other products.

Now's the time to wrap it all up into a quick, summary package. (Or,

if you just skipped here from the beginning, get ready for the punchline.)

Here's the very, very brief summary:

If you're not a "pro" photographer, and you're wondering about model releases, you probably fall into one of these three categories:

Where everyday people can get into trouble (but still not very often), is if they say something about someone that somehow causes him to lose his job, or destroy his life. This has nothing to do with photography per se—it's more about the "text" of what you say> Photos are often used in conjunction with defamatory statements, but it's not the photo that gets people into trouble.

Regarding commerce, if a photo is to be used in a commercial context

that requires a release (note: not all commercial uses require releases),

publicity laws kick in. But this is not well-defined at all, and is

usually where the internet rumor mill opens up, and just about everyone

gets it wrong. So wrong, that they get themselves in more trouble by

trying to protect themselves from something that they shouldn't have

worried about in the first place.

If you haven't done so, immediately read Model Release Primer. That short chapter basically encapsulates why releases are necessary, and who is ultimately responsible if an image is used improperly. The reason for getting model releases is not to protect you, it's to protect those who ultimately license the photos from you. If it were that simple, why do photographers care about getting people to sign model releases? Because more clients will buy a released image than an unreleased image. Therefore, getting a model release is a business decision, not an act of self-protection. (Yes, exceptions exist, and that's also discussed here.)

Even if you are worried about yourself, the practical reality is that

no one is going to sue you unless (a) you have a lot of money that

can be taken, and (b) they have a lot of money to spend on the suit.

For someone to bother with any suit, they need to have a strong case, or

don't mind risking the loss of a lot of money in trying. And because

of (2) above, they aren't going to sue anyone unless they're really,

really upset. (Or, unless there's a lot of money to be had at little

risk or cost.)

The second-most important aspect we examined is the Risk/Reward Analysis Here, the lesson is that you can't just look at things as whether it's strictly legal or not. You have to look at the more practical, real-world considerations. In the soccer game example, if one of the parents has a problem with your showing his kid's face in print, your biggest problem is probably going to be social concerns, not legal ones. You may have the legal right to sell the photos, but agitating other people isn't going to help your business. The point here is that being "right" isn't enough to be profitable.

There's no way to teach pragmatism. You either get it or you don't. One way to determine if you're not being pragmatic is if you find yourself constantly worrying about whether you need a release for one photo without thinking. If you find yourself looking for literal legal interpretations, you're not be pragmatic. If you're trying to pin-point specific arguments for or against something, you're not being pragmatic. There's certainly nothing wrong with contemplating the subtler nuances of the law and having thoughtful discussion about it, but if it affects your decision-making on how to move forward with business, then you're not being pragmatic. Lastly, don't assume I'm suggesting you be carefree about the issue of releases. I'm not—you can make as many bad decisions by being too lax on the matter as well. Pragmatism is finding that reasonable middle ground where the costs and the benefits are in balance. Oh, and in case you missed it, please read Model Release Primer.

Click to recommend this page: |

|