|

Click to recommend this page:

| |

Introduction

Introduction

People often associate long exposures (or long shutter speeds) with

night photography. What is overlooked are the amazing photos

you can get with longer shutter speeds, ranging from 1/15 of a second

up to many hours. What's more, these aren't tricky, and don't require

sophisticated cameras and lenses. Because of the techniques associated

with shooting at varying lengths of (longer) shutter speeds, I break them

down into three categories: Shorter exposures, which go from about 1/20th

of a second to several seconds, medium exposures, which go up to about

a minute, and long exposures, which can be indefinitely long.

Shorter Length Exposures

Shorter Length Exposures

"Shorter" versions of extended exposures are those where you typically

want to capture motion blur of an object or action. You may either

be shooting from a moving object (such as riding a bike, horse,

roller coaster), or you may be in a stationary position taking a picture

of a moving object (like birds, horses, a bike rider, waterfalls,

fireworks, fog). What each of these cases have in common is (most

typically) the fact that they take place during the day. This means you

have a lot of light available, and when there's a lot of light, your

camera's shutter speed tends to be pretty fast. One way to slow down

the shutter speed while maintaining the overall exposure balance is to

use a very small aperture, also called "stopping down." The smaller the

hole, the less the light, the longer the shutter speed to get the light.

Technically, this isn't rocket science. The challenge is the composition.

Because things are in motion, it's hard to frame your picture in real-time

conditions that change so quickly, and deciding when to release the shutter.

Expect to shoot many pictures of the same thing, hoping that one great

shot will appear. One hint about composition is to pay attention to the

direction of motion, since that will be the theme of the picture.

Straight lines, curved motion, forward, backward. It's all about

leading the viewer's eye from a starting point to an endpoint. It may

be subtly implied, or very direct, but it's the motion itself that you

want to convey.

When shooting from a stationery position, something else in the scene

must also be stationary, or the effect is lost. Hence, it is necessary

to keep the lens stable during the exposure to keep those stationary

objects still. For 1/8 of a second or so, one "can", with enough practice,

learn to be relatively still, but even then, it still requires repeated

shooting. If you're on a train, for example, you can use a tripod.

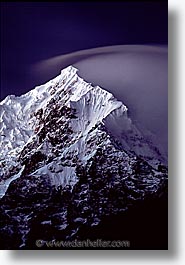

Moving clouds are also excellent subjects for extended exposures. For example,

this photo of Mount Veronica, Peru, shows how clouds appear when they move

over mountains. Shooting just about any night scene with moving clouds can

produce interesting effects, but be careful not to expose for too long.

Given enough time, the whites of the clouds will eventually pass by all the

open spaces in the sky (even if it's never entirely overcast), losing the

"swoosh" effect.

Medium Length Exposures

Medium Length Exposures

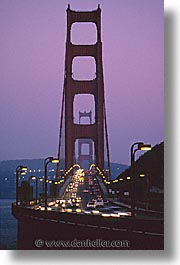

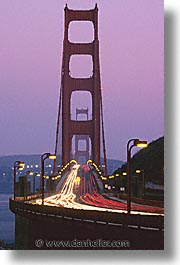

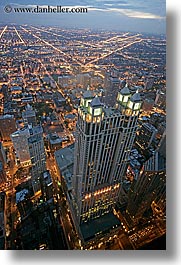

Medium length exposures include those up to a minute or so, and are

therefore the most common type of long-exposure work. The only thing

required is a tripod or other sturdy object. Dusk, dawn and many nite

scenes in cities (or traffic) are excellent candidates for these types

images, because there is ambient light to fill in the shadows, which

balance out the highlights. (Traffic at nite is one of my favorite

subjects.)

As these photos illustrate, streaking lights from cars show a sense of

motion, and are immediately appealing. The longer the exposure, the

longer the car headlights streak. There are many ways you can play with

this effect, and as you get more familiar with the process, you can

experiment with the timing; when you start and stop such exposures has

a great impact on the final result.

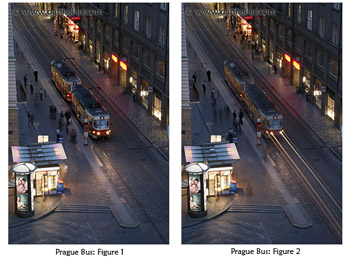

For example, consider the pair of images of the stopped bus. Both were

exposed the same amount of time: 30 seconds. However, the headlights for

the bus on right-hand image appear to "beam" forward. This is because the

bus was stationary for the first 25 seconds before it began to move in the

last five seconds. The brightness of the headlights were captured, but the

bus' movement isn't captured because it doesn't emit enough light itself

(other than its headlights) to affect the longer-term imprint that already

took place. A shorter exposure might not have provided enough time to

imprint the stationary bus, and would have also allowed the brief time it

was moving to have a more pronounced imprint. To successfully capture this

effect, experimentation is critical. (It took about an hour to experiment

with this—mostly involving having to wait for another bus to come by.)

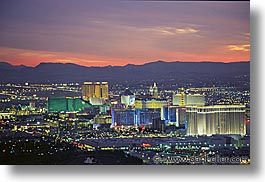

A favorite subject among amateurs is fireworks. While beautiful, they can

be highly unpredictable, so again, prepare to shoot many frames with more

bad pictures than good ones. The main problem is figuring out what exposure

to use. If it's too long, the fireworks themselves overexpose, and if it's

too short, all you get is fireworks, and no background (context). The

only solution to this is shoot for the background—that is, expose as if

it's a nite shot—and try to time your shutter releases so that the fireworks

are either at the beginning, or the very end of the exposure. You'll have

to shoot at least one picture of the scene without any fireworks, just to

gauge what your base-line "nite" exposure is. Once you have that, you can

time the fireworks accordingly. (That is, attempt to have the fireworks

either be at the first or last 5 seconds of (say) a 30-second shot, for

example.) This way, the basic scene will come out right, and the amount

of light from the burst won't be over-exposed. You want at least a second

of it (and up to about five seconds) to get the "motion" of the sparks,

or the photo probably won't come out pleasing. Again, experiment to taste.

Clearly, it's a lottery game to determine when the operator is going to

let off the next one, and it's not even worth shooting when he lets them off

back to back (unless you like the abstract/artsie look). Except for those

situations, I'll shoot every moment of a one-hour fireworks display and be

lucky if I come up with five good shots. And if there's a strong wind—forget

it. Similarly, the smoke can become a visual eyesore if there isn't

enough circulation to cycle it out during the performance.

I always try to compose fireworks to have some sort of foreground

(the people watching them, nearby buildings or landscape). As you know,

fireworks involve bursts, flashes, and streaks, which are all over the

map for making good exposures. Getting an "even" look involves timing.

And that is governed by your noticing how the fireworks are spaced apart

from one another.

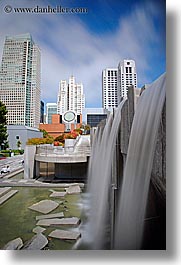

The challenge for obtaining long exposures in the daytime is how to reduce

the amount of bright daylight to allow for a longer exposure. Stopping

down your aperture (as was done for the shorter exposures) won't be enough

for these, because you need to block even more light. The solution is

to use a neutral density (A.K.A., "ND") filter. These filters are tinted

with a "neutral" color, serving no other purpose than to reduce the total

amount of light into the camera. ND Filters come in many configurations,

from one stop of light, up to thirteen stops, where each "stop"

doubles the amount of time of your exposure because it blocks twice as

much light as the previous stop. So, a picture that would normally taken

at f16 @ 1/30 second can turn into a 30-second exposure with a 10-stop

ND filter. People have been known to photograph the sun traveling across

the sky all day using two 13-stop ND filters stacked on top of each other.

I usually carry with me a 5-stop and a 10-stop ND filter. And that's where

the fun begins for things like waterfalls or fog, to name two examples.

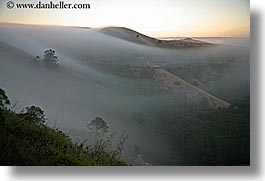

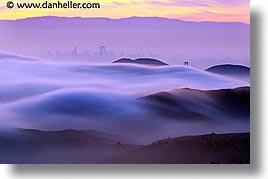

Fog is rarely motionless, so it is often a great subject for extended

exposures because its movement often appears as "flowing cream" when low

to the ground. (You tend not to get this effect if the fog is hovering;

this type of photo is best shot when you're away from the fog.)

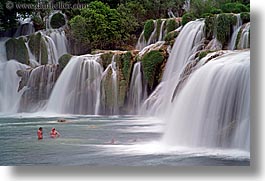

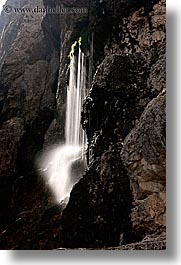

Flowing water has a similar effect as fog, and it's much easier to find.

Whether a river, or crashing waves, any type of liquid movement is a good

candidate for longer exposures.

Long Exposures

Long Exposures

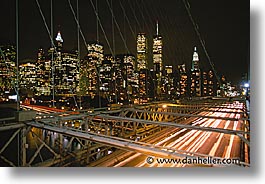

Long exposures are great for capturing cityscapes, like star trails,

moon-lit valleys and lightning. For this discussion, we'll only be

dealing with pictures shot at night, and where exposure times can last

from several minutes to many hours. (If you set your ISO rating high

enough, you can also get good night pictures with only a few seconds of

exposure. These may look nice in small format, but digital noise from

most cameras will probably yield poor results if you blow them up to

larger prints.) In all the cases discussed here, a tripod and cable

release are required (because you won't be able to keep your finger on

the shutter release without moving the camera). For this photo of the

Tower Bridge in London, I also used a "mist filter."

One of the first tricks people like to play with using night photography

is using exposures so long that the scene actually looks like a daytime

shot. The longer the exposure, the more "daylight" the picture will

appear to have. This only works for rural landscapes where there is either

no artificial light, or where the light can be turned off. Otherwise,

expended times will cause those lights to overexpose. The rest of the

scene is lit naturally by the moon, which fills the sky with sunlight.

(Remember, the moon is just reflecting sunlight, albeit at a reduce rate.)

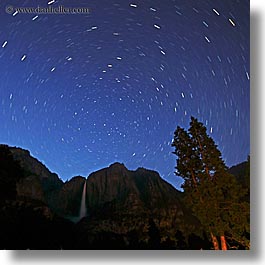

Night exposures of waterfalls are especially stunning, as shown by these

pictures of Yosemite Falls. Shorter exposure times not only capture the

night imagery well, but you can shoot more pictures than if you had to wait

around for the longer exposures.

Whether shooting on a moving object, or from a moving object, using

a flash is very effective for freezing a moment in time, while also

capturing the motion. The flash imprints the foreground only

(because flashes are often limited to about ten feet), so its important

to compose the photo accordingly. So, do not expect the flash to capture

far-away objects. As for the foreground, even if other light happened to

be captured with the motion blur, chances are that the flash will be

more prominent. The taxicab photo is a good example of this, but other

common uses are shooting bands in concert, or people dancing. The flash

will capture a still image, but the extended exposure (ranging from

1/8 of a second to several seconds) will add the necessary "movement"

feeling to evoke a sense of what's going on.

You can use flashes during long exposures creatively, for example, by going

inside a building and bursting the flash by hand. The trick is to

direct the flash away from the camera, but toward a wall or object that

faces it. (Again, remember the ten-foot rule—most flashes aren't strong

enough to illuminate objects further away.) You typically burst several

times from inside a structure to make it appear that its interior is lit.

The example here uses a flash covered by a red "gel" (over-sized filter).

These long exposures require some experimentation to get right, but the

effect is pretty, not to mention unique.

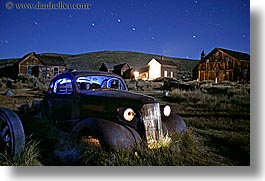

Given enough time and creativity, you can really go hog wild. For this

photo of the junker 1930's Buick, I placed a flashlight inside the car,

and gave it a blue gel. After a little while, I turned it off, and placed

it inside of each headlight of the car.

For larger spaces, or for use on building exteriors, consider buying one

of those mammoth-sized spot-lights at large home-improvement stores.

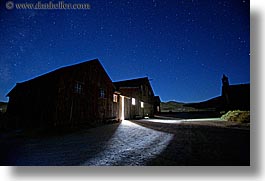

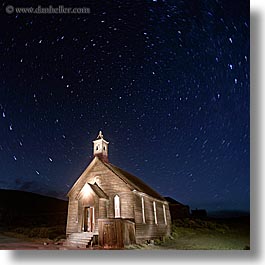

For the photo of a church in the Ghost Town of Bodie, California, I

"painted" the exterior of the church with a naked (no gel) spotlight just

as thought I had a real paintbrush. I "stroked" the building from top to

bottom with the spotlight, making sure the whole thing was covered. It

only took about 30 seconds to paint it, but the entire exposure was about

7½ minutes long. In the other photo, I painted each side of the

house with the spotlight, but this time, I used a red gel for one side,

and a blue gel for the front. the exposure time was well over an hour

and a half, but it only took two minutes to paint it with light.

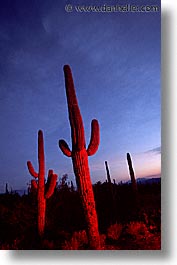

If you don't have a flashlight—or, at least, not a strong one—consider

the tail lights of your car. This is how I light the cactus in Tucson

Arizona.

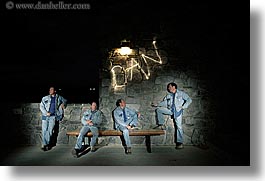

If you really get bored at 3am, try self-portraits! For this single

picture (lasting 54 seconds), I started by "writing" my name with a

small pen flashlight on the wall. Then I sat on the bench and had a

friend burst a normal camera flash my way. I did this four times in

total, as I moved from one side of the frame to the other. Again, this

sort of thing requires extensive experimentation, because it's hard to

know where to "be" so that you don't overlap yourself on top of yourself.

(It's a neat idea to try, but I found it doesn't really work.)

On the technical side, these techniques are no different than any other

form of extended exposure photography. The creative aspect is finding

interesting subjects and figuring out how (or whether) to light them.

Speaking of bursting light onto a subject, there's nothing like using

nature herself to do the heavy lifting and adding the creative spin.

Obviously, lightning's dramatic effect is worthwhile, but don't just

set up your tripod in the direction of a lightning storm and hope to get

good shots. Compose as though you were photographing any landscape,

whether a cityscape or a natural backdrop. I just set the camera up

(where it wasn't raining), pressed the button on the cable release, and

waited anywhere from 5-10 minutes, depending on whether (or how much)

lighting would strike. Metering for exposure times is similar to that

of fireworks. The frequency of the lightning will affect the overall

exposure, and there are no guidelines (other than experimentation)

for how much exposure time you should allow.

Using Film

Using Film

There is still a large community of people who use film for long

exposures, and for one good reason: the batteries in digital cameras

don't last during very long exposures (like star trails). So, many

photographers use film because those cameras use very little (if any)

power. There is one issue, however, that almost all film suffers from:

reciprocity failure.

Chemicals in the film react to light proportional to the amount of light

exposed to it. That is, they "reciprocate" the light. Reciprocity

Failure simply refers to when the film fails to produce an image that

represents the light that was projected onto it. Simply put, the longer

the exposure, the more you have extend the time your camera meter says to

get the correct image on the film. This is easiest to see in black and

white film: if you meter a scene that shows a proper exposure of 1 second

at f8, then doing the math, you should be able to double the time and the

apertures to yield exactly the same picture: 2 seconds at f16, 4 second

at f/32, and 8 seconds at f64. All of these should produce precisely the

same image. However, for some films, "reciprocity failure" begins to

emerge gradually as those exposure times increase, which may require

(for example) extending the time exposure, even though the meter doesn't

say it should. For example, doubling of time to 16 seconds at f64 to

get the same result you should have gotten using 8 seconds.

What's going on is that the chemicals in film don't react to light

consistently across time. This doesn't happen during short shutter

speeds—those used during typical daytime photography, which explains why

most people don't see this. Even at longer shutter speeds, the degree of

failure tends to be minimal and people overlook it. (It's also easy to

fix in the printing process, so it's rarely a concern.) However, as the

during of time expands to longer and longer exposures, the film begins

to fail more dramatically, so you need to add more time than you think

you should, just to get the picture you want.

For black and white film, it's simply a matter of extending the duration

of time. However, color film is more complicated because it has more than

just one chemical: it has at red, green and blue to deal with as well.

(In fact, most films have more, but you get the idea.) Here, the reciprocity

failure affects all of these chemicals, and, making things worse, they all

react to light differently than one another. As it turns out, reds and blues

failure much more quickly than green, causing long exposures tend to look

very green. The longer the exposure, the more out of sync these colors

appear to be.

Different films use different chemicals for colors, and some films

add more "stabilizing" chemicals than others to reduce this effect

somewhat. So, while every film "can" suffer from some degree of

reciprocity failure, not all are equal, so there is no uniform way to

solve the problem across the board. Those who shoot Fuji Velvia 50,

for example, has a much more dramatic problem with "green shift" than

Provia 100F does.

Because film's reciprocity to light fails gradually over time, and

because different film types (and even similar films from different

manufacturers) also vary, it's impossible to predict the final result

from any given picture. You can use colored filters to "help" correct

the problem, but the inconsistency of the films and the filters mean that

you're never going get precisely a color-balanced shot like the pictures

you see here. Whenever you correct for one color, you throw off another.

The goal, therefore, is to find the filter that approximates your picture

as closely as possible—finding that middle ground—at which point,

you have to correct images digitally, where you can individually

manipulate each of the red, green and blue hues in the overall picture.

One might think that, if you're going to fix it in Photoshop anyway,

why bother with filters? The reason is that fixing colors digitally

is just as imprecise as using colored filters: you change one color,

you affect the others too. You get much better results and the process

is easier if you start with colors that are as close to "correct" as you

can get, and then go from there. Which leads us to a discussion of filters.

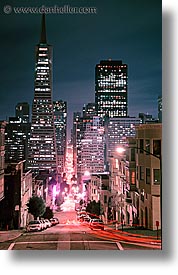

The FL-D filter is normally used to correct for the green hue from fluorescent

lights. However, I use it to correct for mild reciprocity failure in some

moderately long exposures using slide film. For longer exposures, FL-Ds

are often not enough to correct the green as necessary, so I move to a

30cc Magenta filter, as shown in the Night photo of Montgomery and Green

Streets in San Francisco. The fluorescent lights in the buildings are

white, but the purple-ish hue affects the otherwise correctly lit areas

of the scene. Using Photoshop, one can correct for this, but this raw

image gives a better sense of you'd get without any correction.

Choosing the best filter can be done, but it could be an effort of

futility to get perfect. Each film type has its own table for reciprocity

failure, which you can find this in the box that the film came in, or

you can look up on the web. Ironically, print film (negative) tends

to suffer less than slide film, and the blueness of Tungsten film also

doesn't have this problem that I've seen.

More To Discover

More To Discover

To see more pictures using long exposures,

go here.

Click to recommend this page:

|

|