|

Click to recommend this page:

| |

Introduction

Introduction

Wouldn't it be nice if there were a game show like "The Price is Right"

for photography?

"Ok, contestants. Our first photo is to be licensed to a company for use in their brochure, printing 5000 copies, worldwide."

"Bob, I would license that image for $200 for that use!"

Bzzzzzt!

"Sorry, Dan, but that photo is worth $3000 for that use!"

(Huge gasp from audience.)

"Ok contestants, this next item is the same photo to a different company, for use in a magazine ad running one year, for a circulation of 1,000,000 units."

"Bob, I would license that photo for $3000!"

Bzzzzzt!

"Sorry, Dan, but that photo is worth $250 for that use!"

(Huge "HUH?" from audience.)

"I don't get it, Bob. Why is it less than the other use?"

"Different client! That's all they'll pay because otherwise, they'll get a different, but worse photo from a microstock agency."

Finding the right price points for selling photography or bidding on

an assignment is the Holy Grail of the photography business. What do

you charge for licensing an image for an ad in a magazine, a billboard,

or for a local merchant's Web site? What about pricing a photo shoot of a

parade for one of the corporate sponsors? How about a wedding? No matter

what the product or the service, pricing is the most daunting problem

facing all photographers in their first years, and it seems there is

no sure-fire method to finding what works. The natural thing to do is

research price charts or guidelines, but as the industry has evolved and

competition has grown, such data points are no longer reliable. What's

more, it's not that simple. Even veteran professionals get frustrated

by the volatility in pricing, not just among different clients, but in

the way the same product can vary dramatically from one case to the next.

Most pro photographers and websites that attempt to assist in pricing

photography approach the subject as a matter of fine-tuning negotiation skills.

But you cannot teach negotiation strategies. It has to be learned

through empirical experience. More importantly, it's imperative that

this experience be a part of a much broader career strategy. One with

specific direction and intent. Any given business act (shooting an assignment

or licensing an image) should be part of that longer-term strategy for it

to be beneficial.

Most photographers don't think long term—they want to shoot and get

paid. And that's the reason why most photographers fail at the business,

and why most who try to help them fail at their advice.

The reality of the marketplace is that photography is a commodity, and

the gap between the perceived "value" of the product between the buyer

and the photographer is too wide. You cannot close this gap simply

through negotiation strategies. The problem with most pros' advice

is that it side-skirts this very reality.

When the career goals and strategies are well-developed and articulated

in one's mind, new and different ideas, goals and objectives get weaved

into negotiations, which turns out to have win-win benefits. That is, what

might seem like a "bad deal" to a short-sighted photographer who only seeks

the highest return for an assignment might actually be quite beneficial to

the longer term career path—which itself yields higher financial returns.

This concept is discussed at greater length in the chapter, Photography and Business Sense.

The unmentioned variable in this concept is marketing. It not only has

an impact on pricing in the short-term negotiations, but has feedback-value.

That is, the non-financial benefits associated with having gotten the

gig (or the license agreement), which adds credibility and increased

perceived value to the photographer for the next client, contract, or

negotiation. These small, incremental successes build up over time, and,

when combined with other acts in the career-building process, add to the

longer-term financial growth.

In the end, marketing strategies frame how a product is packaged and

presented. Who does that presentation has so much more to do with

perception of price than what most people think (or want to believe),

that to understand pricing, one must also have a firm grasp on the

nature of marketing. That discussion is covered in Marketing your Photography Business.

Nevertheless, with all these elements involved in the recipe, the one

take-away message one must commit to memory is this:

"One doesn't just find a pricing chart and expect to sell pictures with it."

The entire sales process, from the initial marketing and presentation,

to the final closing and collecting of money, contains elements that all

have to fit together symbiotically. This delicate relationship has to be

consistent with the photographer's most fundamental business model. For

example, if a photographer produces a low quantity of images per year,

and focuses on a narrow market segment, then it follows that his pricing

structure should command a high price per image, or he won't yield much

income. So, he'll have to have very strong and focused marketing and

packaging for his business to justify such expenses to his potential clients.

Hence, asking for a high price for images makes sense here, and his success

will be determined by how effectively his other business strategies support

these prices. Conversely, a photographer that produces a huge number of

images per year would be well advised to set up an infrastructure to move

a lot of images to a lot of very broadly defined clients, in which case,

each image is priced pretty low. Trying to claim high prices per image

would require a lot more time spent with clients that would take away from

the time necessary to deal with the rest of the volume of images.

The question that many photographers face when getting started is that

they don't yet know where on that broad spectrum between high-volume and

low-volume they will ultimately fall. Invariably, such photographers (and

readers of this text) are probably unclear on their longer term objectives,

but are at this very moment faced with a sales opportunity for an image

and they need some guidance on guidelines. To that, I can only provide

this simplistic advice: take whatever you can get—it doesn't matter.

That's right, if your career is going to be long and illustrious, it really

won't matter much in the end if you found you got way underpaid in the

beginning. The real value is the important lessons you learn while diving

into the water and learning to swim. The mere value of the experience itself

trumps whether or not you get it right in the beginning. Of course, you want

to learn the most you can, which is why you need to continue reading this

chapter.

This chapter looks at the various strategies associated with pricing

images or services. This includes more than just pricing "policies," which

may be rules of thumb for price adjustments based on certain variables.

"Strategies" exist at a higher level, where policies are modified according

to an intuitive sense for sales as unique transactions.

To understand pricing, one must understand the sales cycle, which

starts with the product itself, then how it is marketed, and lastly,

interactive negotiations (otherwise known as the sales process).

For purposes of this chapter, I will only discuss the commercial realm

(licensing images and assignments and services). I will not talk about

photos sold as "art" here.

(For that, see Selling Photography Prints.)

What makes selling art difficult is its intangible qualities; it has

little "functional value," unlike software whose value can be analyzed

quantitatively by the amount of work produced. Photography's biggest

disadvantage of all the art forms is its perceived value. A famous

and rare print by Ansel Adams may only go for several thousand dollars,

compared with millions garnered for a painting by an equally well-known

painter. Making up for this handicap is photography's ease and low

expense in reproduction. (Sadly, this may be the reason why its value

perceived to be less, and why it's seen as a commodity.)

On the flip side, these characteristics become benefits: more people

can more quickly identify and understand a photograph than a painting,

making it more suitable for commercial use. That it can be easily

reproduced makes it easier to sell in quantity in broader markets.

But, these contradictory qualities don't always work in tandem.

For example, the value of an image is higher if it is being used to

advertise an expensive vacation package to Hawaii in Conde Naste's

Traveler magazine, versus an image used for a local newspaper ad for

a pet shop. The fact that it's an image has, in itself, no real

value. Its perceived value is defined more by the buyer. (Hence, the

seller has to de-tangle his emotional attachment to it.) Therefore, the

product must be regarded as something that has no value until it is

presented to the appropriate buyers in an appropriate market segment.

This is vague right now, but that's why it's important to understand

marketing.

The critical step in the sales cycle is marketing. Yes, before pricing

comes into play, the most important component of selling photography is

how it is packaged and presented (or, the name recognition of the artist,

if applicable). Marketing can pre-empt the perceived value of the product.

Since marketing and pricing go hand in hand, they must conceptually

agree with one another. Thus, the marketing "message" must be customized

to the target buyer. The product itself is clearly important, but as we

all have seen (and are frustrated by), even the most mediocre images

(and photographers) can sell quite well if marketed properly. This isn't

a new concept; it also applies to software, vacation rentals, horoscopes,

and political candidates. So, above all get your marketing right. It is

strongly advisable to read the Marketing your Photography Business before this chapter,

if only to grasp the bigger picture here. But, marketing can only go so

far—it "sets up the kick," as it were. To really score, the performance

must come from you personally. This comes in the form of:

For any pricing structure to work, it must lie within the circle

of plausible possibilities. That is, the customer has to believe

it. Setting arbitrary prices can be intuitively seen by any buyer as

just that: arbitrary. And you can't set prices high with the expectation

that you'll just negotiate from there—such a strategy will only alienate

more prospective buyers. You can't begin the sales process if you don't

start with the right pricing structure. As mentioned in the beginning

of the chapter, most people think of pricing as static data that can

be listed in a chart. Indeed, there are such charts, and you may end up

making some. But how you make them, and how you use them are important

parts of the larger strategy. So, we must begin by establishing a

plausible pricing structure for your products in your marketplace.

I propose the following foundation:

"Pricing a photograph involves finding that range of values that most of

your likely buyers are willing to pay."

There are several elements to this statement that need to be made part

of your sales paradigm.

First, I used the words, "a photograph."

First, I used the words, "a photograph."

I didn't say "Pricing photography...", I said, "a photograph." Because

each image is different, it will likely be of more or less value to any

given client. You must establish a mindset that disassociates photography

from the "commodity" pricing model so you can perceive sales as a

process. This won't always apply, of course, and there will be many

times where you sell directly from your published price list (discussed

below). Negotiated sales requires breaking from the "price list"

paradigm, and that will happen more often than not. Many photographers

resist doing this, because they feel they would be regarded as weak

negotiators. That is definitely not true. Weak negotiators are so, not

because they "deviate" from the price list, it's because they do so

poorly. Accepting the fact that price lists are not etched in stone

requires a mindset that you are not selling a bunch of identical widgets,

nor to equally qualified clients.

Next is the phrase, "range of prices."

Next is the phrase, "range of prices."

It's counter-productive to think that you're going to set price points

that (a) people will either accept or reject, or (b) apply to the broader

global market. Selling is ultimately about negotiation, so your pricing

tables should really be thought of as starting points for discussion. It's

true that if you're selling "commodity products," like calendars or even

prints, one rarely deviates from the price list. However, when it comes to

a consultive sale, where someone wants to license an image of individual

and unique uses, variables come into play that don't apply to the

commodity market.

For example, consider an image to be used at a size of 18x22", on the

box for a game being distributed in the Pacific Northwest. There's a

price somewhere for that—what, we don't yet know. Let's also say the

request for the image is for two-years. That's a price adjustment.

Let's also say they just want to use it in black and white—another

adjustment. You don't go to a price list for this, and although you can

establish "pricing policies" to cover various modifications like this,

you optimize return by understanding the "importance" the client places

on the product. The greater their need, the greater the value of your

image, the more you can edge those "policies" in your favor. Conversely,

the lesser value your client places on it (or the lack of "uniqueness" of

the image, etc.) the more willing you may be in relaxing those policies.

The policies are considered your legitimate vehicle for justifying

pricing proposals. Yes, it will happen that you need to lower your price

to make a sale, but you need to save face; you can't just lower the

price arbitrarily, or it'll appear your pricing was arbitrary. Pricing

policies help protect your legitimacy because they give you "good reason."

This is a fancy way of saying negotiation.

In summary, don't look at price lists strictly as the high point, after

which you expect to come down. They are best thought of as "typical uses,"

where different terms and conditions can make the prices rise or fall

accordingly. Your published "policies" may even articulate this point.

(This sets up the buyer for expecting to negotiate.)

Last is the phrase, "most of your likely buyers."

Last is the phrase, "most of your likely buyers."

As noted at the top of this section, you can't expect a price list to

apply to the global market. Granted, that's a very loose and vague

term. We live in a global market, but I'm not referring to geographical

boundaries. You must identify your target market, preferably one

that you know quite well (perhaps because you came from that industry

in a previous career). Your pricing cannot be arbitrary; it has to be

based on either empirical experience, where you know the business model

of your buyers (consultive sales), or it has to be researched, where you

understand the buying behavior of the market segment (such as commodity

products). Whoever the buyer is usually has a preconceived notion of the

value of what they're buying before they see your product, and you have

to either meet those expectations, or convincingly justify a deviation.

A discussion of this is found in Photography and Business Sense.

When photographers seek out pricing tables based on published reports

of historical sales, they fail to realize that those prices are based

on negotiation sessions for specific uses, by specific clients, for

specific markets. Having data about ranges of prices for very narrow

market segments may be useful, but the narrower the segment, the

less likely it is that there is a sufficient sampling of data points

to give validity to any of them. In short, they're all circumstantial.

We'll address this again later.

Drawing on the information above, we can identify three major components

of the sales process:

- The Price List

- Pricing Policies

- Negotiation

Each of these can be considered a separate stage in the sales strategy.

Once potential clients have responded to a marketing effort of some

form and an image they're interested in, the first thing they see is

your price list. From there, they usually establish contact, where you

discuss various policies. (These can also be printed as part of your

price list.) At this point, negotiations begin. Let's take each of

these independently.

Establishing a Price List

Establishing a Price List

Figuring out initial price points is the hardest part, because you

need to establish that circle of plausible possibilities we discussed

earlier. So frustrating, this is, that you may think you should have

taken up cooking instead. (I'm just kidding; cooking isn't nearly as

fun as photography because it requires a kitchen, which is dangerous for

those of us who are cleaning-impaired.) So, where do you establish your

initial price points? Doing research on this is like having a severe

mental disorder with hundreds of voices in your head: you don't know whom

to believe! Charts, research reports, coaching software, prices quoted

on other photographer's sites, what your friend, Ed, told you, peer

pressure (what other photographers on the internet claim), and industry

associations all have something to say about the subject. Rarely will

any of these sources agree on actual numbers, but they'll all claim to

be right. The thing is, sometimes they are right! Given the thousands

who constantly chime in with opinions, such as, "Hey Steve! Your advice

to quote $500 for that image was right on!" It can sometimes appear

that someone knows something more than the others. When it comes to

anecdotal evidence, remember this quip:

"Even a clock that doesn't run is right twice a day."

You can never base business decisions on anecdotal evidence, whether

yours or that of a select group of people. You have to see in much

broader terms.

There are various philosophies about the most effective strategy for

determining appropriate price points. Most photo-industry groups

point to formulas for determining prices based on historical models,

for example. The price for an image licensed to a magazine was typically

based on their advertising rates. For a full page ad, the theory held,

if the magazine charges X to an advertiser, your price would be a

percentage of X.

While this certainly feels fair and beneficial to both sides of the

deal, this pricing strategy is not as well received (if even recognized)

to a degree necessary to recommend this method. Using this form of

"formula pricing" will yield just as arbitrary results as reading your

horoscope will predict the future (unless you're a Libra and your moon

is in Aquarius). While it's true that such formulas were the standard

for the industry decades ago, and some media companies still use such

methods for determining pricing, these exceptional cases cannot be relied

upon in the general open market (unless you're a Leo).

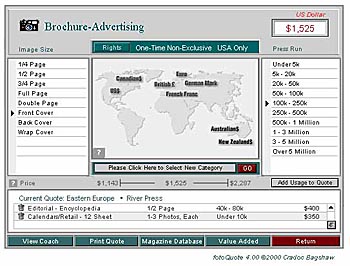

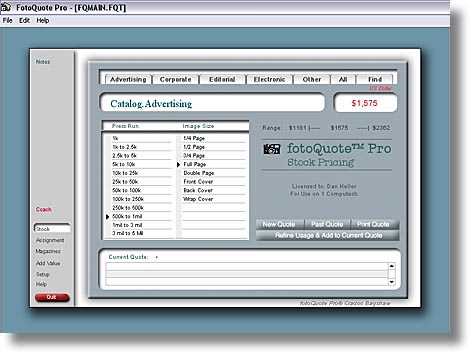

There are software programs that can be purchased to assist in coaching

pricing strategies. An example of this is one called Fotoquote, which

is built from a database of statistical pricing from sources in the photo

industry during the previous year. You can look up hundreds of different

photo uses, with thousands of different variations on those uses, and see

how the prices range from one extreme to another. To be sure, each of

these provides some useful context by which you can gauge pricing

guidelines, complete with discussions on people's empirical experiences

for such markets.

There are software programs that can be purchased to assist in coaching

pricing strategies. An example of this is one called Fotoquote, which

is built from a database of statistical pricing from sources in the photo

industry during the previous year. You can look up hundreds of different

photo uses, with thousands of different variations on those uses, and see

how the prices range from one extreme to another. To be sure, each of

these provides some useful context by which you can gauge pricing

guidelines, complete with discussions on people's empirical experiences

for such markets.

There are too many problems with this data, including:

- Surveys only go to professional photographers, agencies, and companies

that buy from them. Truism #1 in the Photography Business states that

this is such a small and disproportionate representation of the entire

market, that the data itself fails statistical integrity.

- The data obtained is entirely voluntary; there is no oversight

whatsoever on the data's validity. Because of truism #1, asking

"photographers" how much they got for any given photo license is like

asking fishermen how big their catch was at the lake on Saturday:

hands spread a little wider every time they tell the story.

- Even if one were to accept that the data only represents the

narrower market segment of professional photographers and media buyers

the number of respondents still represent a statistically insignificant

percentage of that target population.

- Most sales are the result of negotiations based on discrete

conditions that cannot be generalized.

During a time when most image sales were done by agencies, and purchases

done by a limited set of buyers, there would be less price variation,

which may give more credibility to the reliability of this data. But,

as the internet opened up sales to a broader array of sellers and buyers,

consistency and reliability of data goes out the window. Not only are

the variations of both sides of the transaction too broad to conclude any

kind of price stability, but the expectation that such a consistency can

exist is naive. Therefore, relying on any kind of price quoting system

that isn't the direct byproduct of your own experience at selling

is worse than arbitrary. It's like trying to learn how to ride a bike

by being on the bike with someone else that already knows. The real

learning process doesn't even begin till you try it solo. Riding with

someone else gives a more deceptive sense of balance, thereby making it

harder to learn on your own when you finally get around to it.

Still, the search for some basis for pricing is desirable, and while

I would partially agree, I raise the second reason the numbers aren't

justified: many license agreements are often based on multiple images,

multiple uses, non-standard sizes, or any number of complex exceptions

that outnumber the "normal" rates described by a price list. The real world

of image licensing so rarely is based on simple text-book like scenarios,

that the price lists, once again, are deceptive to the point of destructive.

Does that make programs like Fotoquote and other price lists invalid?

The answer varies, depending on how new you are to the business.

A positive spin is that it's a tool, and you have to know how to

use it wisely for it to be effective. Most people don't, which is

why most will will be harmed by it than helped. For the extremely

experienced photographer who already knows the nuances of the industry,

but has come across an unusual circumstance where it'd be helpful to

know how someone else dealt with a similar situation, such data can

provide abstract insight that only a seasoned pro can interpret with

the proper number of grains of salt.

When it comes to assignments, whether "day rates" for an ad agency,

or the services of a wedding photographer, the same kind of data is

available, but again, it's not that simple, but the reasons for it

are more easily understood: a photographer doesn't wake up one day,

decide to shoot weddings, and then look up price lists in charts. More

often than not, he's familiar with the local market and what the going

rates are. Whether he starts as an apprentice for another photographer,

or has some other affiliation with the industry, one who starts his own

wedding photo business usually knows something of existing rates.

That should be the process for any photographer breaking into his chosen

fields of photography, whether journalism, advertising, or even the adult

market. No industry is simple, so it's best approached from the inside.

If you have an opportunity to quote an assignment and are completely lost

about where to start the bidding, you should review the checklist from

Photography and Business Sense. This won't help you determine a good bidding price, but it

will remind you that the value of the assignment itself is probably

worth far more than the money you may receive from it. (Therefore,

you should do what you can to get the gig.) That's not to suggest you

should bid low, just bid "appropriately," keeping the bigger picture

in mind. If you lose the opportunity, you could be losing more than

just the money you didn't get.

For what it's worth, I still get requests for price quotes that have

me scratching my head. Sometimes, the best thing to do is just ask the

obvious question: "Do you have a budget for this?" And if they squirm at

that answer, squirm back: "I can't give you a price quote unless I get

a better sense of what your overall project is like." People always

know how much they want to spend on the entire project, if not the

bits and pieces of it (like photography). Once you get a sense of

their project, it's easier to figure out what their expectations are.

If they're going to use a photo for a banner, and the banner costs

$5000 to make, they clearly find importance on the photo. If it's for

a 1/4-page ad that only costs $200 in the local paper, that's another

piece of data for you. The rest is somewhere in the middle.

If you are reticent to establish your price points because you think

they'll be set in stone, don't worry. I've modified my price lists many

times in my early years as experiences dictated and refinement was

necessary. In fact, as market conditions change, price revisions are

inevitable. So, this is an ongoing process.

Once you establish an initial price list, the next step is to formulate

policies for how and when to deviate from those lists. These are

usually simple, codified terms, such as:

- Per-image discounts for multiple images

- Price tiers based on image sizes

- Multipliers based on volume or distribution

- Per-year reductions for multi-year terms

- Incentives for encouraging behaviors that help you

(such as listing your Web address in photo credits)

- Premiums (mark-ups) to discourage behaviors

that don't help you (like not listing your Web address).

Pricing policies are necessary because most clients are going to have

an infinite number of variations that you cannot write into the basic

price chart. It would be confusing, let alone unwieldy. Buyers expect

some sort of pricing policies to be in place, which even have the added

advantage that such policies are regarded as "accepted price variations."

For example, if someone tries to negotiate down a license fee, you

could counter that he's getting a bargain because you've dropped

the "multi-year multiplier, which would have added an additional 25%

per year." He may still negotiate, but you're on a stronger footing when

you have policies to justify positions. He may continually beat you

back, but policies act as protective fortresses. Through all this, though,

remember that you still need to sell the product, and your price just

may be too high. Therefore, a finger on the pulse of reality is advisable.

As you can see, discussing pricing policies borders on:

Before engaging in any discussion on negotiation, one must have

read and understood Truism #5 in the Photography Business: all photographers are not

equal, and are rarely paid similarly for the same work or image. How much

you are paid, whether for an assignment, or a license fee for an image,

has everything to do with how well you negotiate.

While negotiation is a test of wits, and you can perform better or worse

based on your command of communication (written or oral), it's important

never to forget what you're negotiating about. It's not about the product,

it's the perception of value, as discussed earlier. This is not a

straightforward science, because it doesn't start out having anything

to do with your images. It's the sense of value that the client has for

the use of an image—any image. If the client has

an ad to produce, there's a sense of value the company has for the

photo that will eventually become part of that ad. Some clients value

text, others layout, others "imagery." Determine what's important to

that client before you enter into negotiation, but no matter what, understand

that you're not going to change this perception. You may be completely

correct in your client's poor marketing sense, and that he should value

images more highly in his overall message, but not everyone feels this

way. If he does, that's great, but you're still in the same boat: you

have to convince him of the value of your images (or the one(s) he's

selected). Where you expect to end up, however, must take into account

the client's abstract sense of value for images in the first place.

Once you know the client's general perception of value, there is number of

things you can do to influence his perception of your images. At

the top of that list is who you are. The better you are known

in your given market, the more value will be perceived by those

in that market. (This is why it's important you target the right

market in the first place.) This isn't just about how well known

you are for photography, nor does it even require your name to be

recognizable. (Although, all of those certainly help a lot, as you

know.) The broader point is that the better you know the client's industry

(part of the "who you are"), the more legitimacy your arguments carry

when you discuss business.

The next most important thing is how critical the image is to the client's

need. If the image is to be used to promote a highly priced or

image-branded product, like a cruise ship by a major cruise line's

brochure, it's going to garner a much higher price than the same image

used by an editorial magazine that writes about one of the trips from

that cruise line. Same image, different use, different client. Hence,

different perceived need. Where it gets more complicated in when multiple

variables are at play.

To illustrate a more realistic example, let's consider two scenarios. In

each case, we have two photographers, each of differing skills and

backgrounds. One shoots head-shots of corporate executives, the other

shoots travel photography for vacation magazines.

Scenario 1

Scenario 1

A company wishes to hire each photographer to shoot its building

for the cover of its annual report. Neither photographer has extensive

experience with architecture, but the "portrait" photographer has

already worked with the company photographing its executives. (Hence,

he and his prices are known.) The company asks the travel photographer

for a competitive bid.

Scenario 2

Scenario 2

A travel outfitter wants to hire one of the two above photographers

to shoot a hotel that will be used in an upcoming brochure. Like the

portrait photographer, the travel photographer also has little experience

shooting architecture, but the outfitter already has experience with

the travel photographer, and the travel photographer's prices are known.

Now, consider each of these questions for each scenario:

- How does each photographer compare in the eyes of the hiring companies?

- How about their bidding prices?

In a sense, you could say that the "job" is identical: shoot the

corporate headquarters building. Shouldn't the pay be the same?

Unless both companies know each other and exchange notes, the likely

case is that their price expectations are going to be based on the

fees of the photographer they know. They're asking for a competitive

bid as a sort of validation check—a form of "due diligence," as it were.

Think about the different ways this could play out and hold that in your

mind as you consider the next case.

Assume that the travel photographer is perceived as the "better" of the

two (by both companies). Now consider how that affects the two questions

above. Here, the complication adds a "reality twist" that many people

underestimate. Once "need" has been established, the question is how it

affects perception of price. That expectation is based on the history

with the known photographer in each scenario, but is complicated by the

fact that each photographer's skill varies. Now consider these questions:

How do the photographers bid, knowing that the other is involved?

Does the better photographer lower his rate because he knows he's

competing against a lesser-skilled photographer who may have lower

rates, and he doesn't want to lose the bid? Does the lesser-skilled

photographer lower his rates for the same reason? How do the photographers bid, knowing that the other is involved?

Does the better photographer lower his rate because he knows he's

competing against a lesser-skilled photographer who may have lower

rates, and he doesn't want to lose the bid? Does the lesser-skilled

photographer lower his rates for the same reason?

Do clients think they may be at risk if they hire the lesser-skilled

photographer and not getting what they really want, thereby prompting them

to pay the higher rate for the better photographer? Do clients think they may be at risk if they hire the lesser-skilled

photographer and not getting what they really want, thereby prompting them

to pay the higher rate for the better photographer?

Does the client use the lower price point from either photographer

to negotiate against the other? Does the client use the lower price point from either photographer

to negotiate against the other?

If you think you know the answer to these questions, you're not thinking

wisely about this sort of thing. There is no way to predict how people

think and feel about this stuff at face value—you have to know them to

understand what they think. What's their risk aversion? What's their price

sensitivity? How important is it? As for the photographers, they too

have challenging questions to ask. Should they lower rates in order to win the

assignment? Should they keep rates higher to maintain integrity in their

pricing? However you look at this, remember one thing: there is no

universal truth about how to play this strategically.

The example above illustrates how perception of price and value play

into the decision-making processes on all sides. Pricing "policies"

are useful for handling whether to add or subtract a little here and

there for variations on use. But, as you can see, it has nothing to

do with how you handle negotiations.

Sticker Shock from the initial price list is probably the biggest

reason sales don't happen. And it isn't always because prices are high.

Clients can dismiss products because they're too inexpensive, too. For

example, the rage over royalty-free images on CDs were initially hot,

but time has proven to most serious buyers that the images they get are

pretty useless. The $300 or so that they spent isn't the real cost, it's

the lost time associated with searching volumes of CDs, only to come up

with nothing that upsets clients more.

Furthermore, sticker shock isn't always from the client; you might

dismiss a client who offers a price you feel is so low, it's not worth

negotiating. When you do negotiate, how do you find the middle? What

is the "best" price? Again, review the checklist in Photography and Business Sense for other

benefits beyond just the money you receive: you don't always need to reach

the highest price, just the best price.

Fotoquote Ratesheet for Catalog Pricing

|

For example, look at the following price chart, where it indicates a

price point of $1500 for a full page ad. What do you do if you get an

offer for $250? Do you turn it down because you're under the impression

that it's worth more? Which "truth" came first? The amorphous "statistic"

of $1500 from Fotoquote? Or the tangible offer of $250 that you

know you'll receive if you accept it? It's a good question, and one that

has very impassioned arguments on both sides.

Some clients actually do this: they dismiss price lists and negotiations

completely and just offer a price. This is actually fairly common

among bigger publishers or those who license images frequently. Here,

the negotiation is easy: you accept or reject. (It may or may not be a

good deal, but it is easy!) Here, the business decision changes a little.

There's no question that by not taking the offer, that's $250 you

didn't get. The question is what are the longer-term ramifications of

this decision? One argument is that you've established a lower price

point, making it more difficult to get a higher price from the same client

in the future; or, that you've set your expectations unreasonably low,

and that you will underbid future opportunities, undermining your own

business. Many who work in the industry would also curse you for doing

so, arguing that you erode prices across the board, affecting not just

your own lower rate, but that of the industry as a whole.

The counter-argument is not so straightforward. First, you never know

what the reality of pricing is till you try it yourself. Everyone

in the business has stories about how they dramatically underbid a

sale (or many of them) when they were just starting out. In each case,

they chalked it up to beginner's naiveté, that if they'd just

"known better," or were more confident to stand their ground, they

would have gotten the better price. While it's comforting to believe

it's as simple as that, there's more to it. Sure, confidence and other

elements to negotiation play a huge role, but you can't manufacture such

a quality out of nothing and expect to use it to your benefit. That is,

you can't just stand firm and expect it to work.

For my business model, anything that requires time is costly, and

I want to be paid for it. Whatever I have to do to close a sale is

work I'm not doing for any other purpose than that sale. Once the

sale is done, the time and work I invested is lost, and that's lost

opportunity to be building my business in a much broader sense.

Even the process of negotiation is time-consuming. The more work it

requires, the more money I'm going to charge. Negotiations start on

my price list, then I get to know my client (this isn't a drawn out

process; it's a short exchange of emails), and then it's about how much

time I have to spend.

Broadly speaking, I like to confine any work I do to things that

contribute to my business as a whole. When I work on my Web site, that

work enhances my entire business. When I do research, I am getting new

information that eventually translates to optimized prices. When I produce

marketing materials, I do so in a way that I can reuse them over and

over. Anytime I have to do something again is time wasted. Similarly,

immediate payment speaks loudly, because I hate having to bug people in

email about late payments. When I can spend time doing things that

generate new revenue, I'm happy. Slow me down, I'm unhappy and I charge

money. (Ok, I'm happy then too, but I still charge money.) I stand firm

when I know I can stand firm.

Seasoned professionals learn the subtle nuances and other cues that may

suggest when it's time to stand firm, or how to maneuver the client in

a way that makes the price more persuasive. Moreover, these cues are so

subtle, they don't always know when they've sensed it. It's similar to

looking at a human face that has a wide-eyed look. Is it fear? Is it

surprise? Is it anger? Is it laughter? One can't always articulate what

it is they see, but there is an intuitive sense for it that we develop

over time that just knows. The same is true for negotiation: just because

you may start out with lower bids, doesn't mean that you could have done

any better. Moreover, it doesn't mean that low bidding in the future is

a bad idea either. You just have to develop the sense for it.

An example that illustrates how my thinking applies to a "low-bid" offer

follows:

I happened to get two calls at the same time from two different people:

one in Kansas, and one in New York City. Both were realtors, both dealt

with high-end real estate property in their areas, and both wanted to

use a (different) photo for a 4x6" postcard used for direct mailing to a

targeted mailing list. The NYC realtor sold properties only over $3M;

the Kansas realtor's properties maybe would get to $250K. By fortunate

coincidence, I talked to the Kansas guy first. He looked at the pricing

guidelines on my site, and paid the listed rate of $645. The NYC

realtor wouldn't even consider it. She wanted only to use the image in

exchange for her putting my name and website (in small print) on the

card. As most clients will tell you sooner or later in a negotiation,

"your name will be seen by thousands of people!" (Clients always use

this as a form of negotiation to beat down prices. They also believe

they know how to market you better than you do.) Anyway, there was

just no way she was going to pay a dime over $100 for the image. But,

as I've pointed out, that's $100 I would otherwise not have at all.

You're probably assume I took the $100. Before I say, think about what

you would do and why. Think of all the reasons for and against both

decisions. Ok? Ready? The envelope please...

I didn't take the sale to the NY client, probably for reasons other than

what you predicted. First, while it wasn't a main issue, there was an

unusual problem in that I didn't immediately have the image in digital

format, ready to go. I would have had to go locate the slide, scan it,

and photo-touch it for dust and color-calibration before giving it to

her. This often takes long enough that no sale is worth less than

$300 (for me).

The more important reason was that she was just a difficult person.

You never really appreciate how costly it is in time and other intangibles

to deal with such people till you do it a few times. You quickly learn

that it's never about the money; if they have a problem or an issue,

you have to deal with them. A lot. If you think they were difficult in

negotiations, imagine how they'll be as you continue with business.

Whatever their problem is, it won't be an easy one to solve, because

they often have issues well beyond that of business. Difficult people

are so for reasons other than business, and they will continue to be

difficult as long as you continue to work with them.

The third criteria, which can apply to many more types of sales,

was that I had no future opportunity with this client. She was a

realtor that didn't license images often, so I had no incentive to

give her a discount. I've had clients that are in need images on a

regular basis, and these customers deserve (and get) price breaks.

In some cases, people "promise" to be future clients, and I always

counter with, "great! So, I'll give you a discount by selling you

multiple images at the same time (now), and deliver the future

images to you when you need them." This always shows their true

colors. (Hint: I've never had a long-term client actually tell me

he was going to be before the sale.)

The nature of the photo business is that your photos are your assets

that you sell to make money. But assets have value, and can therefore

be used as barter currency to get "opportunities" that promote your

business. You may hear many photographers say, "never give away images

for free," but that's an overly simplistic viewpoint. Instead, it should

be "don't give your images without recognizing some value in return."

This often comes up because photographers are often offered a photo

credit in exchange for using an image in a catalog, for example.

Clients want to minimize their costs, and they know that photographers

need help getting visibility. It's their perception that the photo

credit in exchange for the image is mutually beneficial. Some in the

photo industry say this is always bad, because it devalues your photos,

and makes it harder for other photographers to keep their prices high.

None of this is true. There's certainly nothing "wrong" with giving

away photos for use by a client in exchange for something that isn't

cash. The question is whether what you get in return actually contributes

to your business growth or evolution. Is a photo credit a good barter

exchange for your photo? During a time when the best (and only) way to

market yourself to prospective buyers and agencies was to have a strong

portfolio of name-brand clients in great glossy-looking catalogs and

magazines to show that you had experience and panache. But such marketing

techniques these days is limited to a tiny portion of the photo industry

these days, mostly fashion and advertising photographers. These days,

the usefulness of a portfolio is waning along with film itself. You

may still find many old-school pro photographers who still use film,

and still use portfolios, but the vast majority of new photo business

"development" is done digitally and on the web. What this has to do with

pricing of images is simply that sales and marketing go hand in hand.

Marketing opportunities may affect the price you charge for a photo,

even to the point of free.

Giving your work to clients is fine if their use of the image actually

helps promote your business. Catalogs don't do that. Why? Because photos

buyers don't look at catalogs, and the use of portfolios is less

common (or effective) in self-promotion. Consumers look at catalogs,

which means that you could conceivably permit a free use of the image in

exchange for the photo credit giving your web address (in a font size no

smaller than the rest of the text on the page). Having your website listed

is far superior to your "name" because that's like a free advertisement.

Well, it has value if your photo business involves the web and you

target consumers. (If not, then it's not such a great value.)

Another way to use "free" in proposals is to offer free use of your photos

on their website in exchange for their paying for the print uses. Here,

you could stipulate that the web use include a link back to your site.

A third alternative is to let them use the image for free so long as they

purchase another one of the same or higher value. This is a successful

way to rope clients in and keep them coming back. Of course, you also

have to prepare to execute this agreement properly—never ever let

a client use the future tense as part of an agreement. That is, don't

let them say, "we will license another image at some future date."

They will almost assuredly never do so. Even if it's written into a

contract, they don't care. Instead, make them pay today, and they can

have the use of this image today and another image at a future date when

they choose. This way, money is paid and if they flake out on their

free image, then that's their loss, not yours.

When I got started, I've used techniques like free use of images in

exchange for free or discounted travel. Today, I still engage in giving

away photos or other services if I feel the opportunity I'm getting in

return ultimately leads to more or better business. But what I considered

"valuable" yesterday is not the same as what I do today. No pro should

ever get out of that mindset.

You should always look at any "exchange" in terms of how it grows or

contributes to business. It isn't always cash, and when it isn't,

understand the value of what you may get in return and weigh it

accordingly. If you ask, "should I give the image in exchange for a photo

credit," and you genuinely don't know the answer to that, then the answer

for you is no. Your business may evolve someday to the point where

such a barter might, in fact, be valuable. The same strategy doesn't

work for everyone. And that's what it all boils down to: strategy. Know

what it is you need or want, and be willing to barter in exchange for

those things. Unless you know you need it, you don't. Don't try to

be like a chipmunk, hoarding things that you think you might need in

the future. Your cheeks can get pretty big and you'll invariably make

poorer choices, thereby passing up better choices that lead to better

opportunities later.

Pricing is the hardest part of the photo business. You start with a

target market segment, then create your marketing strategy, and then you

go through the sales process. In each of these steps, you're going

to fumble around a bit before you get it right—they do not have to

be executed to perfection before you go to the next step. What you'll

find, if you play it smart, is that successful pricing is the result of

knowing your client's business model and the subtler nuances in their

negotiating styles. So, let's review:

Don't set pricing expectations on single data sources.

Don't set pricing expectations on single data sources.

While pricing charts provide great information to know and reference, you

need to dispense with your emotional attachment to them. When you're

getting started, consult many sources to get a handle on various price

structures, but don't expect to reliably use any of them right off

the bat. Keep in mind all the truisms discussed in the Photography Business, as these

will help you maintain a business mindset and perspective.

Consider the cost of doing business.

Consider the cost of doing business.

All things considered, if it takes 30 seconds to email an image to a

client, that's worth a lot of money in the form of time and overhead

saved, than if you have to locate a series of potential images that you

have to send to the client, who then chooses among them. Even a paying

client can be costly in indirect ways if you're not careful, so be sure

you don't find yourself chasing what appears to be a hot prospect, only

to find out that it's a dud. (And don't worry, it's easy to accidentally

fall into this; I still do from time to time.)

Consider the benefits of the ancillary aspects of your business.

Consider the benefits of the ancillary aspects of your business.

There is value in the form of marketing and "name recognition" for

certain clients, and you should consider the intangible benefits of any

given sale beyond just the money. While I don't place much value on some

"photo credit" exchanges (I just "require it" out of hand, and don't

allow it to become a negotiating token), there are always exceptions.

As such, certain barters are more valuable at one point during a career

path than they are at another.

It's all about Volume.

It's all about Volume.

When it comes to total annual revenue, there are two basic sales

models: lots of volume of low-priced items, or fewer sales of high-priced

items. The key is all about infrastructure and administration. If

you work better alone and with clients on a one-on-one basis, you're

probably better off with the higher-price/low-volume sales model. If

you are good at setting up and managing workflow processes involving

employees, you'd be better at the high-volume/low-price model.

If I had to part with any last piece of advice, it'd be to maintain

critical thinking. I found that simply knowing how the industry worked

gave me better negotiation skills and a more credible platform to state

my case for higher rates. But, the reality is that pricing is and always

will be, an amorphous concept that we never really grasp. You just have to

get better at it without expecting to perfect it.

Click to recommend this page:

|

|