|

Click to recommend this page:

| |

Introduction

Introduction

When I got serious about making photography a real business, I felt I

needed to migrate from the amateur equipment I had, to pro-level stuff.

In the middle of doing extensive research, I got a call from a client

who asked me to shoot a cycling trip for them. I didn't have time to

buy the expensive "pro" gear, so I was worried that I was ill-equipped

for the job. To my surprise, the pictures came out fine. In fact, since

I took those shots in 1997, I still sell many of them today. Now, years

later, I have pretty expensive gear that I never even thought I'd ever

get, let alone use. But, the reasons for upgrading aren't what I would

have thought back then, either. I'll get into those as we go through

this chapter.

The issues you'll face when choosing appropriate camera equipment for

your photography business may not be what you think either. Obviously,

there are many different kinds of photo businesses, and mine is but one,

so my intent is not to tell you what to buy, or to emulate what I do;

it's to help you think about the issues that actually matter (and which

don't) so you can make better purchasing decisions. As with all commodity

products, there are many models and brands from many manufacturers,

most of which may be suitable for your needs, so don't assume there is

only one right answer for you. Instead, just understand that as long

as you know why you may need something (or if you don't), you'll feel

confident in whatever decisions you make.

Note: it is assumed you have reasonable experience shooting pictures

(even as a hobbyist) to put this chapter into context. If you're still

in the learning phase on the subject, see What camera should I buy? and What Camera Should I Buy? (Part 2)

for primers on the basics of photo equipment.

So, back to my story: there I was, looking to buy a new camera body

for the purpose of building my new photo career. In the extensive

research that I was doing, it took a while before I found a great

little understated quip someone uttered on a photo discussion board:

"Camera bodies don't affect image quality; lenses and film do."

This cleared the field of many choices right off the bat. Instead of

looking for camera bodies, I realized I should be looking at lenses

first. However, in digital photography, the "film" is now part of the

camera body, so the body has become important again. While there are

clearly many quality film-based systems, the context for professional

photography discussion today is more about digital. So, we begin

with some preliminary discussion on what's important in digital cameras

and why.

The most important part of a digital camera is its digital sensor, which

is measured by resolution and dynamic range. Resolution refers

to the total number of pixels that the sensor has, and the dynamic

range refers to its sensitivity to light. (That is, what detail it

sees before it loses information due to excessive light, or the lack of

it.) For example, if you take a picture of a scene with the sun in it

and a shadowy area, the important question is how much detail can you see

across the range of brightness. Many cameras perform very differently in

this regard, despite what you may see in photo magazines. In most print

ads, you see pictures of pretty models under studio lights. These photos

portend to illustrate dynamic range by showing bright colors mixed

with dark ones. The implication is that the camera can pick up details

across the entire spectrum, but this is deceptive. The discerning viewer

knows not to confuse light range with color range. These pictures

are misleading because the actual range of light is not being tested,

just the color. Any device can produce these images because of the

nature of the conditions under which they were shot. I have done

exceptional prints with a $100 digital camera back in 2001.

(See Pictures taken with Fujifilm's Finepix 2600z, 2800 and A201 Digital Cameras for examples.)

The real test of dynamic range is how much detail can be

seen in all parts of a picture, like the following:

The range of light that a camera (or film) can capture is called

latitude. The broader the range of latitude, the more detail in

can pick up in extreme highlights or shadows. While all cameras have

some moderately acceptable degree of latitude, here's a case where the

cliché applies: "you get what you pay for." Yes, the more expensive

digital SLRs (DSLRs) really do have higher resolution and can capture

a broader range of light than their less-expensive counterparts. I can't

recommend any here, because the technology is evolving so fast, whatever

I mention will have been obsolete by the time you read this. So, read

up on product reviews in reputable photo magazines and websites to see

which cameras are currently hot and why.

With that information, here's where smart business sense comes in:

don't oversimplify. If you're going to buy a new digital camera or

migrate to digital from film, choosing what's right for you requires

understanding your business needs. If you're only shooting school

portraits, you can easily get away with low-end equipment. Wedding

photographers can use a good mid-range camera, but sports, travel and

advertising photographers will probably need the highest-end cameras

available. Can you figure out why? The factors that place each of these

examples into their respective categories will be the factors that you

need to understand before choosing which digital camera is right for you.

To answer this question, let's apply what we just reviewed about resolution

and dynamic range. School portraits rarely require prints over 8x12,

or 11x14, which just about any low-end digital camera can produce.

Similarly, the lighting conditions are fixed (because you have studio

lights), which a low-end camera can easily handle. In the case of

weddings, you may make larger prints (up to 20x30 in most common cases),

but you also have a more dramatic range of shooting conditions (sunsets,

etc.). But these are often leveled out by the constant use of a flash

(and other additional lighting equipment) that these controlled

environments can accommodate. Most mid-range cameras can easily handle

such conditions. The last category of sports, travel and advertising

photographers, finds many cases where extremely high resolution images are

necessary. Printing for billboard use, is all the example you need.

Similarly, extensive dynamic range is required due to the unusual and

unpredictable shooting conditions for most of these photo categories.

What's more, other more advanced features may be important, such as high

frame-per-second shooting speeds and weather resistance, both of which

are usually only available in the highest-end cameras. These are two of

those "unexpected" reasons that I referred to in the beginning of the

chapter on how it is that I was forced into higher-end gear myself.

The right business decision is not so much about getting the "best"

digital camera, it's buying the right camera for the type of business

you have. Because I am a travel photographer, my need for resolution and

dynamic range forced me to stay with film till digital sensors could rival

what I could get from a high-resolution scan of a quality slide. That day

came when Canon came out with the EOS 1Ds Mark II, a 17 megapixel camera

whose resolution yields an image 4992 pixels wide (or tall). Also,

it's not just about resolution, there are many other valuable features,

not the least of which is that the sensor has an ISO range that goes

from 50 to 3200 with minimal noise.

Make no mistake, my business still runs successfully with my huge library

of film stock, much of which has been scanned. So, one shouldn't presume

that you can't run a successful photo business on film. You can, so long

as you convert your film to digital format for all the other business

reasons. Even then, it's still more economically (and technically)

beneficial to migrate to an appropriately configured digital camera.

And yet, those who shoot film know of its benefits (their clients may

require it, or they still make prints in the darkroom, or there may be

other artistic justifications), so again, you need to determine what's

right for you.

Medium format cameras have been part of the professional photography

world for decades, mostly for one reason: the size of the film is twice

as large as 35mm film, yielding exceptionally sharp and brilliant

pictures. There's no question that the thrill of getting that big format

film on the light table is incomparable; anyone feels like a pro with a

medium format camera. The usefulness of MF cameras, however, has waned

since the quality and resolution of high-end 35mm digital cameras

surpassed that of medium format film (re: the section preceding this

one). While you can buy digital backs for medium format cameras, their

enormous cost doesn't really justify the marginally better images they

produce. Therefore, the uses for this format is limited to smaller,

specialized fields of photography.

This doesn't mean that medium format cameras are useless, or that

they will go away forever, but, the argument in favor of them is a similar

one to that of film: if you're already invested in it, if you know and

understand the system, and if you've used it for years, you might as well

stick with it.

There are so many different kinds of lenses to choose from, one can

write an entire book just listing them all. To understand what kind

of lenses are most appropriate for your creative and/or business needs,

this section will cover some of the most basic lens types that will

handle most shooting conditions. Remember, this discussion is not about

technology—it's about choosing lenses that yield marketable images. I

won't be talking about the quality of lenses; I'll be discussing how each

category of lenses produces different types of marketable images. What

brand or model you choose requires independent research.

Before we begin, there's one more thing to remember: the sensors in many

consumer-level digital cameras are smaller than the frame sizes in film

cameras. The impact this has on the final image is similar to what

you'd get if you used an overhead projector to project an image onto

a screen that's too small for the wall. Whatever's outside the screen

is simply lost, or "cropped." Yet, when people make prints of their

pictures, the final image is still printed on the same 4x6 prints that

they'd get with 35mm film, so one loses the perspective that the image

is cropped; instead, most people perceive the image as being "zoomed in"

or "magnified." This optical illusion isn't entirely accurate, and

it's important to discern the difference here because the effects of

"magnification" and "cropping" are two entirely different things

optically, which has a great impact on the decision you make for which

lenses you may want to use or purchase.

For example, a picture taken using a fisheye lens (discussed more later),

yields an image that really bends and bows light dramatically from

the center to the edges of the picture. Because it's still a standard

35mm lens, the optics are still projecting the same bowed image onto

the sensor. The part of the image that lands on the sensor is exactly

the same as what you'd get on a traditional 35mm camera, but what falls

outside of the area for those smaller sensors is simply lost. You can

imagine what this image would look like cropped—you would still see the

fisheye effect—just not as much around the edges because it would be

cropped. Whereas, if it were "zoomed in," then you'd see the exact same

effect all the way around, just "closer" to the subject. And that's

clearly not what's going on with these smaller sensors.

As a result, the industry has adopted phraseology that matches

this optical illusion. That is, digital cameras are said to have a

"magnification factor" from standard 35mm cameras, even though that's

technically incorrect. Because most digital sensors are about 2/3 the

size of the full 35mm frame, that magnification factor is about 1.6x

(even though, in reality, 1/3 of the picture is cropped around the edges).

In the end, it means that a 35mm camera with a reduced digital sensor

and 20mm lens, will yield a photo that looks like it was shot with a 30mm

lens. This can be extremely confusing and troubling for those who expect

to get really wider perspectives in their pictures. What some people

choose to do is buy wider-angle lenses just to compensate for this

"magnification" factor. But remember, "zoomed" pictures yield a very

different sense of distance and proximity between objects in the field

of view than pictures that are merely cropped. Getting a 10mm lens just

so you can take pictures that said to be 16mm equivalents are going to

yield very strange looking effects you don't expect.

The good news is that this is a temporary problem. The reason it's with

us now is the result of weighing camera quality and price. Larger,

full-frame sensors are exceedingly expensive to produce, and the

only way to get cameras to the general public at low prices is to

produce these smaller sensors. As technology evolves, though, camera

manufacturers are slowly evolving their product lines to make sensors

that match the 35mm frame the lenses were designed for. In the interim,

some manufacturers are making wider lenses than those already on the

market just to provide enough "wide angle" for customers that need an

immediate solution to their existing cameras.

The bottom line is that you should make sure you find the lens length

that meets you image needs, and not necessarily take the lens length

measurements discussed in this chapter as precise recommendations. If

you want to achieve a particular look taken with any given lens length,

remember to calculate in the "1.6 magnfication factor" so you purchase

the right lens.

For the rest of this section, I refer to lenses according their lengths

in standard 35mm frame measurements. That is, a 20mm lens will yield

a photo that, optically, yields an appropriate picture, which is what

I show here. I do not show images shot with consumer-level cameras

whose sensors crop images.

As we move forward, we need to address a subject that affects every

photographer: blurry pictures from hand-shake. We've all suffered

from it, and some great photos can be lost because of this simple, but

annoying problem. The reason is similarly simple: the longer the focal

length of the lens, the more susceptible it is to shaking when you take

the picture. The rule of thumb is that the shutter speed needs to be as

fast as the lens is long, assuming an ISO rating of 100. So, a 500mm lens

needs a shutter speed of 1/500sec. A 200mm lens needs a shutter speed of

1/250sec (cameras don't shoot at "1/200"). This may not be an issue in

bright, sunny outdoor situations, but go into the evening, or indoors,

and you've got problems. Even then, a shorter 50mm lens needs a shutter

speed of at least 1/60sec, which is susceptible hand-shake vibrations

for many photographers.

To deal with these situations, you are forced into doing one of the following choices:

Use a "faster lens."

Use a "faster lens."

Named as such because they allow you to shoot at faster shutter speeds,

they can do this because they have wider apertures, like f2.8 or f1.4.

The tradeoff with this is the wider your aperture, the more limited your

depth of field. If it's not bright enough, you may have to "open up"

so wide that your subject may end up out of focus unless your focus is

dead-on. Get it wrong, and you're not much better off than if the photo

was blurry from hand-shake.

Use a tripod.

Use a tripod.

Tripods are impractical for street shooting or scenarios where you've

got to move around on foot.

Use a very bright flash.

Use a very bright flash.

On-camera flashes are great as a "fill" to bring light to shadows

under hats and from harsh sunlight, but they are dreadful when used

as the main light source in evening or indoor photography. (In some

circumstances, you may not be allowed to use one.) For business reasons,

flashes create an unnatural light imbalance, which is makes pictures

much more difficult to sell.

Use faster film, or set a higher digital ISO rating.

Use faster film, or set a higher digital ISO rating.

Both of these options degrade photo quality substantially.

The best pictures are those shot at very low ISO settings (film or

digital) because the grain is smoother and the colors more realistic

and vibrant.

The best solution to this common problem is to use lenses equipped

with "image stabilization" (or "IS") technology. This is a system

embedded into some lenses that use a gyroscopic element that spins in

a counter-direction from the destabilizing movements (like your hand

shaking). Using IS, I am able to hand-hold pictures with shutter speeds

down to about 1/8sec and still get sharp pictures in low-light conditions,

while still retaining a low ISO setting. When you calculate that 30-40%

of pictures that would otherwise by ruined by unintended hand-sake blur

are now saved, not to mention the overall increased quality, the sale of

any one of those pictures could offset the incremental cost of an IS lens.

Of course, IS lenses will not hold the image perfectly still. It does

"drift," much like a spinning top gyrates to keep from falling. This

means that you can still get blurry pictures if you use "too long"

of an exposure. But, 1/30sec and up are often impossible to hand-hold

effectively, so IS still keeps you ahead of the game. Additionally, IS

isn't appropriate for shorter lenses, because their shorter length doesn't

really accommodate the gyroscopic elements necessary for the feature to

work. Just as well, shorter lenses are less susceptible to the problem

anyway; using the rule of thumb, a 24mm lens can allow for a shutter

speed of 1/20 second, which is much easier to do with shorter lenses.

While Canon first developed the image stabilizing technology in 1990

(see patent #4,998,809 at http://patft.uspto.gov/), Nikon licensed

it from Canon until they eventually developed their own version in

2004 (patent #6,778,766), calling it Vibration Resistance. Canon's

technology is somewhat more advanced in that it can also provide

left-right stabilization independently, which is necessary for sports and

nature photographers that track moving objects. A few other camera makers

are jumping on the bandwagon as well, albeit more slowly. Suffice to say

that it will eventually be found everywhere, but like anything else,

quality will vary considerably.

If you're thinking that there are innumerably more factors involved in

lens quality that should be considered beyond IS, you're absolutely right.

Image quality is highly dependent on glass quality and other lens construction,

but since most of the top-name brands have high quality glass suitable for

most photo business needs, it is only this issue of image stabilization

that rises above all others as a priority. The good news is that both

Canon and Nikon make good, quality lenses across the board, so you're

not going to make a mistake in which you choose. Choosing among these two

competitors puts the decision back, once again, to the digital sensor and

the quality of images they can capture. That technology grows in leap-frog

fashion, where the best bang for the buck oscillates between them on a

fairly regular basis (every other year or so).

Back to lenses, let's review the basic lens rundown to see what's most

appropriate for your needs. Note: depending on your photo business,

some of these may not apply, but the information is still important for

reference.

I'll start with mid-range lenses because those are used in most common

situations: day-to-day snapshots, candid people pictures, landscapes,

dogs, or anything else from a normal viewing perspective. Focal ranges

span from 28mm to 150mm, although many lenses vary (some adding more range

on the wider end and/or longer end). In fact, some lens manufacturers

make lenses that go from 24mm up to 300mm, encroaching on wide angle and

telephoto categories. However, because the main intended range is still

in this middle area, they are considered mid-range zooms.

It should be noted that there is a tradeoff with these ultra-dynamic range

lenses: the wider the range, the lower the image quality on the extremes.

The narrower the range, the better the quality. "Fixed focal length"

lenses (that don't zoom at all) are the sharpest and can yield the best

pictures. But their lack of range makes them less versatile and hence,

less practical for many photographers. (Having to carry more lenses

just to get the broader focal range you need can be impractical, but it

depends on the type of photography you do and your style of imagery.)

The objective is to find a focal range that's wide enough to retain

usefulness, while constructed well enough that it has good image quality.

For me, my main workhorse lens in this category is the Canon EF 28-135mm IS

because it seems to be a reasonable compromise of all these needs, plus it

has the very-necessary IS component that I value. On the other hand,

because its image quality may not meet certain commercial needs, I also

have the Canon EF 24-70 2.8L. Here, the range is more limited, and

it doesn't have IS technology, but it's sharpness makes it more appropriate

from certain controlled situations (portraits, weddings, pets, products,

food, etc.). Many brands and manufacturers have similar ranges, but product

quality varies considerably (and tracks with its price).

Telephoto lenses are best known for close-ups of people or wildlife,

but they're also great for landscapes. Long lenses usually start

from around 100mm and can go on and on. The photo shown here with

houseboats in Sausalito with the city of San Francisco in the background

was shot with a 400mm f/2.8 IS lens, with a 2x extender added on, which

equates to 800mm. It's an impressive shot, and yields good returns in

my business. (Within a few days of putting it online, I sold several

prints and licensed it to various companies for various uses.) All

sounds great, right? Now the bad news: the lens alone cost over $8,000,

and it weighs over fifteen pounds once you factor in the box you carry it

in. What's more, it requires a very heavy and rugged tripod, which costs

a fair amount too. These aren't things you carry in a picnic basket,

or expect to get as a birthday present, but when your business depends

on it, you get it. (Sigh.)

Since it's not always practical to spend (or even use) a big, expensive

telephoto lens, you can downshift to less-expensive lenses that are

lighter and have smaller maximum apertures.

For example, a 500mm f/8 mirror lens from Samyang, costs a whopping

$114, and weighs in at only 13oz., making it perfect for carrying with

you at all times. Slightly more expensive is the 600mm f/8 mirror lens

from Sigma, weighing in a 29oz. Costing $350, it's not a bad deal for

the length. However, both lenses are fixed at f/8, and do not autofocus.

The super-long 500mm and 600mm lengths mean that your image is going to

jiggle like Jell-O on a roller coaster when the picture is taken, so you

need to mount the camera on a tripod. What's more, you'll also need to

use your camera's self-timer to delay the shutter button, because the moment

you touch the camera, the image will jiggle. You'll need to allow it to

settle before the shutter releases. And even then you're not assured of

stillness. The photo of Sausalito and the Golden Gate Bridge shown here

required a shutter speed of 1/250 second, which is far too slow to try

to handhold this image when stuck with a constant f/8 aperture. (Many

failed attempts taught me this lesson, but its inexpensive price

made it worthwhile!)

So, can a $114 mirror lens compare with my $8000 behemoth? Not even close.

Not a single attempt at reproducing the San Francisco photo was sharp

or attractive enough to bother keeping. On the other hand, these lower-end

lenses are useful because these are inexpensive and not bulky. In short,

they're fine for personal use and artistic creativity, and makes a perfect

stocking-stuffer for the photo-enthusiast in your family.

Let's face it, telephoto lenses are most practical and useful when

they zoom. But you have the same quality/range compromise mentioned

earlier: the greater the range of zoom, the more quality degrades.

However, your range of tolerance is better at the longer end, although

your tolerance for what is "acceptable quality" may vary, but many pros

consider the range between 70-300 to be insufficient for their needs. (I'm

included in that group, although my personal favorite is Canon's 100-400 IS.)

You can get a broader range and still maintain quality if you're willing

to live with certain compromises. For example, Canon's EF 28-300 IS

is a dream in every way, except for weight and cost. While it takes stunning

pictures, its scale-tipping 4.3 pounds make it impractical for most

people, and at over $2100, it's not something you'll find under the

Christmas tree this year.

Before I dismiss heavy lenses too quickly, it should be noted that they're

perfect for sports photography. By placing your gear on a monopod, you

can alleviate the need to carry it, allowing you to shoot from a stable

position, while rotating as necessary to follow fast-moving subjects.

For me, my wide angle lenses compete with my telephoto lenses for

usefulness. Because of the shorter focal lengths, hand-shake blur

is less of a problem, so there's no need to put image stabilization

into this line of lenses. Also, because shorter lenses can be wider,

you can get apertures of f2.8 and more without excessive cost, compared

to mid-range and especially telephoto lenses. The main issue to concern

yourself with wide angle lenses is the aberrations of image quality.

I have a Canon EF 16-35mm f2.8L wide angle zoom, which is especially

good for interior spaces, and more so from tight corners. It's amazingly

sharp, and its lens elements reduce flare better than most lenses

I've seen. Alternatively, there is the EF 17-40mm f4 for a slightly

longer zoom range at the expense of 1mm in the short range.

There's nothing unique about Canon in this regard; other

manufacturers have comparable products and price ranges that mirror

this same product line-up, although lens tests of any brand should be

researched before purchase.

For ultra-wide angles, I use the Canon EF 15mm fish eye and, to a lesser

degree, a Tamron 14mm f3.5 flat-field lens. (i.e., not fish-eye).

You can see the results in the images here. I use wide angle lenses for

everything from landscapes to people to general street shooting. There is

no rule for when to use or not to use a wide-angle lens, as that is up to

the creativity of the photographer. One thing to note is that, despite

the fact that the 14mm should be wider than the 15mm, the fisheye lens

actually captures more than the 14mm lens. This is a byproduct of the

distortion of the glass.

As a matter of fact, I absolutely love my fisheye lens and carry it with

me constantly. Sure, it can bend things out of proportion, but sometimes,

that's exactly what I want. Fisheye appearance is good for humor, to

exaggerate, or for creative control. I license a lot of images shot with

my fisheye, so it does provide a very practical and real business use.

But, it can also get unwieldy to those unfamiliar with it. It's very

easy to try to "Get too much" into the scene, making it far too busy.

Rules of composition apply here more than ever: make sure the picture

is balanced and as a featured subject or theme, or you risk making a dud.

Fisheye lenses can come in a variety of fixed focal lenghts, and

experimentation is advised to optimize the fisheye's features. While

the images shown here were taken using a 15mm fisheye, many digital

cameras are not full-frame images, resulting in what effectively is a

cropped image that may not yield enough of the fisheye effect for your

tastes. To compensate for this, merely use a shorter focal length,

such as a 7mm fisheye. While Canon doesn't make one this length, other

manufacturers do, and they fit on Canon bodies as well as other brands.

While the shorter-length fisheye would yield a completely circular image

on a full-frame 35mm sensor, it would look more similar to the 15mm

fisheye images you see here for those digital SLRs that are not full frame.

Digital cameras capture pictures by writing image data onto compact

flash cards. Like film, when it gets full, you have to empty it

out. Therefore, the big issues you'll face are:

-

How much memory is optimal for a digital camera CF card?

-

When on a trip assignment, what do you download the image data to?

-

What do you do with the images after you get home?

Let's look at each of these questions individually.

To evaluate what capacity of CF cards you need, there are several factors

to consider.

What is the resolution of your camera?

What is the resolution of your camera?

My 16 megapixel is technically twice as big as an eight megapixel camera.

Each frame writes up to a 10-megabyte file per image.

Note that higher ISO settings consume more CF memory.

How much do you shoot when you see something you like?

How much do you shoot when you see something you like?

I tend to shoot a lot of frames of a subject once I deem it interesting.

I don't just take a snap or two and move on.

Do you preview images in the camera as you shoot?

Do you preview images in the camera as you shoot?

I very rarely do this, because the LCD screen consumes battery power,

and the process takes a lot of time. What's more, I found that I can't

really trust the details on the LCD—I'd rather edit after I've downloaded

the pictures so I can view them in high res on a computer monitor.

If you preview images as you shoot and delete the ones you don't like,

you will not fill up a card as quickly.

How many cards to own?

How many cards to own?

I only own two CF cards. One is in my camera at any given time, and the

other is downloading pictures from my last full CF card. I then switch

them when the next card fills up. Cards are expensive, and you don't need

more than two if you have an external disk drive (image bank) that you can

download images to. If you opt not to have a portable drive, you need to

have a series of CF cards. You'll have to do the math (price per megabyte)

on the cards and drives to figure out which is the less-expensive option.

I've tried to track it over the past year, and the volatility of prices

and quality products makes it infeasible to pinpoint at this time.

What is your tolerance for being interrupted?

What is your tolerance for being interrupted?

In the days of film, there was nothing I hated more than finishing a

roll and having to stop shooting just so I could change rolls. Those

days are over with CF cards, because now I can buy very high capacity

cards and shoot most (if not all) day without having to change cards or

download pictures more than once. The tradeoff is cost. Higher capacity

cards cost more, but those prices are dropping so fast, it may not be

an issue as time goes on. If you change cards when you fill one up,

the question is how often you don't mind having to do that.

It's impractical to make specific recommendations on CF card size

because of how quickly technology evolves. When I started writing this

book, I used two 1G cards, but I have since upgraded to 2G cards, and

I'm not even done with the book. I now see that the 4G cards are just

about to drop in price significantly, with even faster read and write

speeds. By the time you read this, it could be that 8-10G cards are the

norm. (Incidentally, they've been around since 2001, but at astronomical

prices.) So, I'll advise my usual spiel: research product reviews on the

internet from reputable sources (which also changes rapidly and people

move around in this industry).

When you fill up a CF card, you have to download the photos to something,

until you can eventually transfer them to your main computer where you'll

do appropriate digital editing, captioning, and archiving. Obviously, if

you can download directly to that device, do so. However, if you're in the

field, whether on a day trip or a multi-month vacation, your options are

to put them on a portable device, such as a laptop or portable hard drive.

If you have a laptop with you, that's probably your best bet because

you have some image management capabilities there (if not the same as your

normal workstation at home).

The problem with laptops is that they are larger, bulkier and susceptible

to damage, a condition that's all the more troubling if you're further from

home and won't return for a long time. So, the next best bet is a portable

hard drive. Many people are familiar with data storage devices like the

Apple iPod, but these are inappropriate for digital photography for

one primary reason: you need to see that your pictures transferred

successfully before deleting them from the CF card. For that, the system

needs to have preview capabilities, such as an LCD screen.

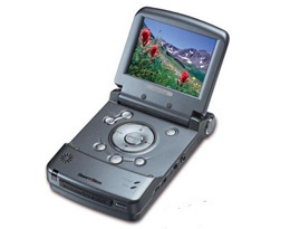

SmartDisk Flashtrax

|

Like anything else dealing with digital photography, choices grow and

quality progresses in the blink of an eye. One year, I chose the

SmartDisk Flashtrax because of its generous screen size and other

non-photo-related features. It also had disk capacity that I needed,

80G, which allowed me to shoot for about three weeks before filling up.

However, within about a year, the device became obsolete. Newer, faster,

better, and less expensive devices (with higher disk capacity) quickly

came on the market. The leapfrog nature of technology yields newer devices

continually, but it's not a reason not to buy something you need now.

Sooner or later, you have to pick something, or you're worse off for it.

Buying photography gear for a photo business involves two basic steps:

determining what type of gear you need, and then finding the best

brands and prices among your selections. Fortunately, the latter step

is extremely simple, thanks to the internet; product reviews are

available online, and the best prices can easily be found using sites

like www.froogle.com. Determining what you need is more challenging.

The goal of this chapter is to help you understand the basic equipment

list and break down the most essential items according to category, and

why they're important. While I have used my own equipment as examples

to illustrate points, these are not necessarily recommendations or

endorsements by any means. Many companies provide excellent products

that get the job done, so you should choose more on tangible factors,

such as how tolerant you are of the weight of equipment (bodies and

lenses vary dramatically in this area), bulk (carrying stuff can be

very burdensome, even if it isn't heavy), usability (there is no

one-size-fits-all in user-interface design), and general aesthetics.

As is my usual advice: never take the advice of a single person, whether

it's a professional photographer, a photo shop sales person, or a friend.

Browse photo-related discussion boards on the net and gather dissenting

opinions as well as advocating views. Negative comments may reveal important

perspective you wouldn't otherwise have imagined.

Click to recommend this page:

|

|